To Have and Have Not

There is a popular bumper sticker on a car along the commute I have taken to and from the school where I once taught that reads:

Equal Rights For Others

Does Not Mean

Fewer Rights For You.

It’s Not Pie.

I have thought a lot about this sentiment as I have walked by it over the years, especially during the current socio-economic situation in this country, and while at heart, I respect and agree with the spirit of it, I’m not sure letter of it doesn’t reveal some important misunderstandings on the part of its car’s owner—especially given the level of affluence in that neighborhood, where such a liberal stance is easy to display at no real cost to one’s self.

Yet maybe…just maybe, there may be some underlying truth to this “pie” thing, and to understand why (and what any of this has to do with education), I need to start this discussion by asking the question: what do we actually mean by “Rights?” Like “intelligence,” it is a term we use rather loosely in our society, and it can mean anything from a privilege (I have the right to get a driver’s license once I turned 16) to an entitlement (the classic “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”). Some have even seen “Rights” as having to do with freedom, such as Roosevelt’s famous Four Freedoms used to validate the Allied efforts in WWII: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, & Freedom from Fear.

I share this latter notion of “Rights” because the Big Four point to an important paradox about why understanding what is or is not a “Right” could mean that sometimes “equal rights for others” may, in fact, result in “fewer rights for you”—as unjust as that may sound to our egalitarian ears. To see why, consider the first two freedoms: like those of religion, speech, assembly, redress, privacy, etc. in the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights, they are all expense-free. There is absolutely no economic cost whatsoever, for example, to every single person having an equal right to speak freely. Hence, for me to argue that others have the right to say what they want does not take away from—or impact in any way!— my right to do likewise.

However, to argue that someone else has the freedom from want…to say, for example, that everyone has an equal right to health care, an equal right to the same quality of education, an equal right to the economic resources needed to live… Suddenly a “Right” has financial costs, and the moment “cost” enters the equation, then equal rights for you can at least theoretically mean the possibility of fewer rights for me. It certainly looks like it has the potential to become about “pie.”

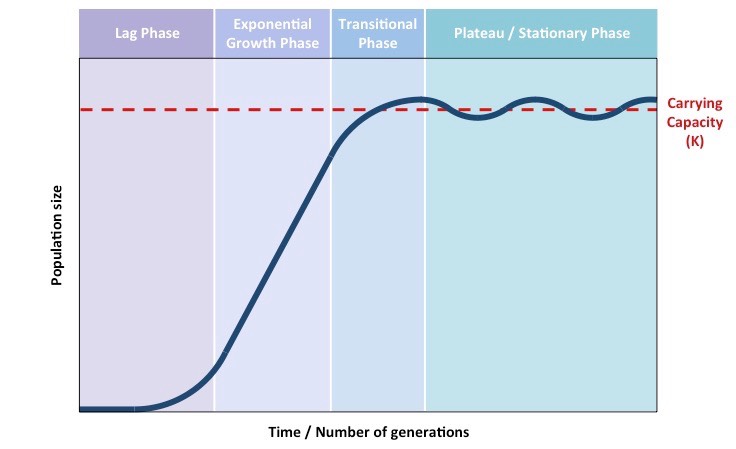

To see how, I need to take a brief detour and introduce my readers to the study of population dynamics. This is the discipline in biology that looks at how various factors in a given ecosystem influence the number of a given species living there, and it turns out that changes in size of the populations of any and all organisms follow two common patterns as they live and reproduce in the environment in which they find themselves. These are traditionally known as the J-curve or exponential phase and the S-curve or logistical phase, and if you look at the graph below, you can see that during the J-curve phase, a population will explode in size. In the real world, this phase only happens when a population of organisms enters a new environment where all the resources it needs for survival are in over-abundance, and it is what is happening with the current situation with the COVID-19 virus: a seemingly limitless supply of humans is available to use to reproduce and so its population soars! We, of course, experience this as ever growing numbers of sick people since we effectively are the virus’ “food.”

No environment, though, has truly limitless resources, and so eventually a population of organisms reaches the maximum size that environment can support (the dotted line on the graph, known as the carrying capacity). It then enters the S-curve phase in which reproductive rates can only temporarily surpass available resources before starvation and competition kill off enough organisms for shorter periods of exponential growth, and the cycle repeats, achieving a homeostatic population size in that particular environment.

This, by the way, is why all the epidemiologist right now keep talking about “flattening the curve.” By slowing the exponential rate of COVID-19 reproducing and spreading among people (i.e. making the slope of that line in the exponential phase of the graph less steep or “flattened”), the virus will take longer to reach its carrying capacity, and that buys two things that are not mutually exclusive: fewer viruses means fewer sick people in fewer hospital beds, enabling us to treat more people to help them live; more time means the chance to actually lower COVID-19’s carrying capacity through the development of better treatments and an eventual vaccine. “Flattening the curve” and the steps to make it happen truly are a win-win!

But what, I suspect some of my readers are asking, does any of this have to do with “Rights?” Or Education? To answer, I need to elaborate first on what that dotted line, the carrying capacity, truly means. In any ecosystem, there are finite amounts of resources; this is true even at the scale of our planet: as boundless as the world’s oceans may seem, there are only so many water molecules on this planet. But if there are always limits on the resources available, then there are also always limits on how to distribute those resources. For example, in a room of 3 people and 9 balls, the distribution might range from a single person having all 9 while the others have none to each person getting 3. But the number of ways to divide the balls up between them is finite, and the same is true for the resources in any given ecosystem.

What this means for a population of organisms, though, is that there are only so many ways to divide an ecosystem’s finite resources among the individual members of that population. That is what that dotted line represents: both the limits on the resources and the limits on how they can be divided. The actual graph, on the other hand, represents the size of the total population, not the number of specific individual members. Hence, while the total population size might drop from one of the S-curve crests due to many organisms dying from lack of resources, there can and will be individuals within the population (or groups of them) who survive the drop precisely because they took extra resources away from the dying individuals. Put simply, because there is not enough to go around in the first place, those individuals or groups who get more of what little there is make it; while those who can’t, don’t.

Yet if a “Right” has costs and even the resources at the level of the entire planet earth are finite…. Now is the picture starting to come into focus? To make it even more so, let’s do a little thought experiment using my home state of Maryland. Let’s say that a high-quality education is a Right that all children in this state have and that the tax revenues of Maryland are the finite resource for this “ecosystem.” We’ll let PARCC test scores and the Maryland School Report Card grades represent how high-quality an education a given group of children are receiving—which I fully acknowledge is a flawed measure at best, but it is a measure—and we’ll compare two school systems that no one living here would contest do not represent two ends of the spectrum of educational outcomes in Maryland: Montgomery County (MC) and Baltimore City (BC). Ready? Let’s begin.

The local tax revenues for MC in 2019 provided $10,807 of resources for each child in their schools, and BC provided $3,703 per child. The most recent PARCC scores in MC are 3 times higher than those in BC, and MC is 10 times stronger on the Maryland School Report Card. The correlation between resources and high-quality education seems rather obvious, which suggests that to get equal educational rights for BC children just might involve fewer rights for the MC kids. It’s starting to look a lot like “pie.”

Yet lest I be accused of misconstruing the data, the picture gets a little more complex because the State of Maryland appears to understand that it might be “pie” and redistributes some of the state tax revenues to try to balance things out. For example, MC only received $5,507 per child from the state in 2019; while BC received $12,223, bringing the MC total to $16,314 and the BC total to $15,926. In fact, by the time federal dollars and all other miscellaneous tax revenues are included, BC came out on top with $17,493 for each student; while MC had “only” $16,859. Furthermore, BC per pupil spending wasn’t even the highest in the state; Worchester County (WC) and Somerset County (SC) topped things off at $18,472 and $18,353 per child respectively.

These numbers, though, would seem to undermine the whole “pie” idea completely since BC and SC schools are among the most underperforming in the state; while MC & WC are among the highest performing districts. It would appear that there is absolutely no correlation after all between access to resources and the quality of education received, and suddenly the “pie” idea about an equal right to a high-quality education in BC and SC meaning less right to it in MC & WC seems incorrect, if not outright false. Maybe equal rights for others when it comes to high-quality education truly doesn’t mean fewer rights for you.

Ah! But like any good rhetorician, I have saved the coup de grâce for last, and in truth, I have left out a significant feature of the total picture. If we return to those local tax revenues, we find that WC, like MC, provided a lot of local resources in 2019 ($13,528 per child); while SC, like BC, did not have much to contribute ($3,618), and what these local numbers reflect is the larger economic disparities between these various communities. MC and WC have some of the wealthiest families in Maryland, and as Brown, Sargrad, & Benner report, PTAs and private donors in MC and WC raise millions of extra dollars for their schools; something the communities of BC and SC simply cannot do. Once again, then, we see that the uneven distribution of finite resources leads to unequal access to high-quality education, and if we believe that the educational rights of all the children of BC, MC, WC, and SC should be equal, then somebody has to give up some of their resources for the sake of the others.

Interestingly enough, that is precisely what the recent Kirwan Commission has recognized about the status of the different school districts throughout Maryland, and in its final report, the Commission lays out the necessary educational reforms needed to address (and redress) the current situation in my state’s schools. But, as I discussed in Chapter 7, our governor has actually raised “dark money” to resist the implementation of the Commission’s recommendations precisely because of its estimated eventual $4 billion per year cost and the perceived threat to the business community, and in fact, during the shortened 2020 state legislative session, the most contentious debates were fueled by the question of where the money was going to come from to fund the implementation of the recommended restructurings and improvements. The bottom line, sadly, is that with certain types of Rights, it is about “pie.”

Yet, what if there’s more than enough “pie” to go around in the first place?

Chasing Beans

It was a cold and blustery out on the playing field, feeling more like January than late April, and I had to suppress a grin: it was a perfect day for this lesson.

“Okay, everyone.” I announced. “As an introduction to our ecology unit, we are going to look at the distribution of natural resources today, and specifically, we’re going to look at the impact humans have on them.”

I handed a stack of cheap, disposable cups to Claire to pass out, and then held up a clear plastic freezer bag containing a bunch of white beans. There were some puzzled looks.

“Scattered throughout the grass are beans like these.” I told them, pointing with my arm. “And your task is to collect as many of them as possible during two five minute time periods. Each bean in your cup will be worth one point, and today’s entire assignment will be worth a total of fifty points. So if you collect fifty beans, you’ll have a perfect score.”

There were some anxious looks.

“And if we don’t find fifty?” asked Chris, hesitantly.

“Then your grade will be however many you do.” I replied.

The ensuing protest was expected, and I held up my hand for silence. I knew I was deliberately lying, but I also knew that the whole point of the actual lesson depended on them initially believing that their grade truly did depend on capturing beans.

“I am completely serious.” I told them. “There are several stages to this simulation, and you will have lots of opportunity to gather beans before it ends. But at the end of class, the beans in your cup is your grade for today.”

There was stunned and perplexed silence.

“Are we all clear about what you’re to do?” I asked. They nodded anxiously, and I put a whistle to my mouth and blew.

The class streaked across the field like fat on a hot griddle, some methodical in their searches; while others studied their classmates and pounced when a pocket of beans was discovered. But they were all intensely earnest in the hunt.

Finally, I whistled again and waved everyone back over to huddle up.

“Gather back around,” I told them. “And very carefully look at the bottom of your cup for a letter. Without spilling your beans.” I waited until they had all done so and then gestured to three spots around me. “If you have the letter ‘I,’ go over there; if you have the letter ‘D,’ over there; and the letter ‘U’ over there.”

The girls collected into their respective groups, and I handed each one a paper sandwich bag and a permanent marker.

“Count the total beans in each group, write that number on the bag, and place everyone’s beans in it together.” I instructed.

Again, they followed my directions dutifully, but as the sole member of the “I” group, MariaLisa looked like she was about to cry. So I walked over and leaned in to whisper, “Trust me after all these months to know that I promise it will be okay in the end.”

She sniffed and nodded, giving me a weak smile, and I turned back to the rest of the groups.

“Everyone finished counting?” I asked.

They collectively nodded, and I recollected each group’s bag before putting my whistle to my mouth again.

“Five more minutes!” I said and blew the whistle.

This time, the girls raced off with even greater urgency, and where they had clamored and complained earlier, now no one spoke at all. They just silently dashed from spot to spot on the field, and when the final toot brought them back together, the sense of dejection was palpable.

“Well, I failed that lab,” declared Em.

“At least you have other people in your group!” MariaLisa protested. “You have a chance of having enough beans to pass. I don’t even have that.”

I interjected. “Everyone needs to do like before, and then we can get out of this freezing wind and go back inside for the rest of the simulation.”

So they counted and muttered and handed me their bags, and we adjourned to the classroom, where I had the girls remain in their groups, asking a member of each to write their grand total on the board. Then I began the true lesson.

“I need all groups to pile their beans in the center of their table.” I announced. “And I need at least two members from each team to get her calculator out and ready to use.”

I waited for this to happen and then proceeded. “Now I need to know what five percent and thirty-five percent of the grand total of all beans in the room is, and I need to know….”

Fingers started to fly as I rattled off a whole series of math questions about the data, jotting answers on the board as students from each group called them out. Then I paused, studying the board.

“Okay…” I said, doing some quick calculations in my head. “Caroline, your group needs to count out 128 of your beans and give them to MariaLisa, and Kate, I need your group to count out ninety-four beans and also give them to MariaLouisa.”

Suddenly the largest pile of beans in the room now belonged to one person–who simply looked bewildered, relieved, and scared all at the same time.

“We are now at the final stage of the simulation.” I said. “And when I say ‘go,’ you will have exactly thirty seconds to do whatever you wish to gather as many beans as you can.” I glanced at the clock meaningfully. “But at the end of the thirty seconds, the number of beans in your cup is the number that will determine your final grade.” I paused to let that sink in, turned to watch the clock, and said “Go.”

A look of sudden awareness came across Chris’ face, and she started to shout “Everybody, wait!” But the erupting chaos drowned out her voice like a tsunami.

They walk into that one every time. I thought, bemused.

“STOP!!” I shouted, and the room went still. Fist clenched crushed plastic cups; scattered beans covered the floor; the place looked like a grenade had gone off.

“Please take your regular seats and take out something write with and a piece of paper.” I instructed. “You need to total the beans in your cup.” I continued. “And write that number at the top of your page. Then take a few minutes to answer these prompts.” I lifted the middle board.

There were several looks of disgust as many of them realized how few beans they had. But as they studied the prompts and started to write, I could tell they were beginning to realize that maybe something else was going on today that simply struggling to collect beans.

“Okay!” I smiled. “Let’s start by easing the tension. There is absolutely no grade for the number of beans you collected today. You can all relax and take a deep breath.”

“I knew he couldn’t mean it!” swore Em. “From the very beginning, I kept thinking ‘Mr. Brock wouldn’t possibly ever really do this to us.’ ”

There were murmurs of assent.

“So why did you do it, Mr. Brock?” Chris asked with a Cheshire-cat grin.

I nodded and gestured to all of them. “Why don’t we start by sharing what you all wrote? How did it feel to be in class today?”

“Well, for one thing, I couldn’t believe you were having us chase after a bunch of stupid beans for a grade!” Dasha grumbled.

That produced a near unanimous declaration of assent, and I waited until I had their attention again.

“How is chasing after beans any different than chasing after points?” I replied.

Dasha just rolled her eyes, but several of them suddenly looked quite thoughtful.

“Come on, Mr. Brock! Points get a good grade, but beans are just…. beans!” She argued.

“Why do you want a good grade?” I asked her, and she looked at me as if I had suddenly gone all stupid.

“To get into a good college!” She stated, gesturing as if that were obvious.

“And why do you want to get into a good college…?” I continued.

“So I can have a good job someday!” She said, flabbergasted. She had taken the bait.

“And you want a good job…?” I inquired, gently.

“So that you can have money to live and raise your kids and….”

“And buy some beans for them to eat?” I asked her, interrupting.

I looked around at all of them as understanding began to dawn.

“How is chasing after beans any different than chasing after grades or anything else you need to survive?” I demanded. “You can at least eat the beans.” I waited for that point to sink in and then continued. “What you did today was what every organism has to do: find the resources to survive.”

I pointed over at the two groups who had lost beans. “But it was also about how those resources get redistributed by human behavior and choices. How did it feel to have to give up what you had worked so hard to collect?” I asked them.

“I was pretty pissed,” replied Lucy, with others in her group nodding vigorously.

“YOU were pissed?” The members of Kate’s group declared. “We lost so much there wasn’t even the chance of having enough beans to pass!”

“What about the ‘I” group?” I interjected. “MariaLisa all by herself? How do you think she felt?”

“Relieved!” came the nearly universal chorus.

“And maybe a little guilty.” Chris added quietly.

Everyone swung around to face her, looking puzzled, and she continued.

“Think about it.” She said. “MariaLisa had more beans than she could ever possibly use, and she could clearly see that your group practically didn’t have any at all. I’d feel a little guilty in that situation.”

There were a few nods of agreement and some speculative looks around the room, and I knew it was time to bring the final lesson home.

“Here’s what the numbers mean.” I told them. “If we treat your class as the equivalent of all the people on the planet, the three people in the ‘U’ group represent the portion of humanity living in the underdeveloped countries. Twenty-five percent of all humans have access to only five percent of the world’s resources. The one person in the ‘I’ group represents how many people live in the industrialized world–places like the United States and Europe. Ten percent of the world consumes thirty five percent of its resources, leaving the remaining sixty percent of the resources for the sixty-five percent of the people in the developing world.”

I paused to let all of that sink in before asking, “How many of you passed?”

Only five girls raised their hands.

“What about the whole room?” I gestured. “Were there, in fact, enough resources so that everyone could have at least passed if you hadn’t all fought for the beans?”

Several started rapidly entered numbers in their calculators, but Chris just raised her hand and I pointed at her.

“That’s why I shouted for everybody to wait.” She said. “I had multiplied all of us by thirty-three in my head and knew that number was smaller than the totals on the board.”

I turned to my number crunchers. “And if you had all shared equally…?”

The disgust in Em’s voice was almost physical. “We could have all earned an 85! We’d have all gotten a solid B!”

Is Too Little “Pie” Inevitable?

As my students discovered that day, where there is enough wealth of resources, the equitable sharing should mean that no one has to have fewer rights so that others can have equivalent ones. The problem is that we live in an economic system that not only does not promote sharing, it is actively antagonistic to it. Mathematicians studying capitalist, free-market economies have discovered that the best models for describing how wealth gets distributed in such economies always leads to its inevitable inequitable distribution. “In fact, these mathematical models demonstrate that far from wealth trickling down to the poor, the natural inclination of wealth is to flow upward, so that the ‘natural’ wealth distribution in a free-market economy is one of complete oligarchy” (Boghosian, p. 77) and, therefore, total economic inequality.

Returning to our earlier example, it appears that if the 3 people decide to trade and sell those 9 balls, eventually one of them will end up with all the balls and the other two with nothing. It is why today the best estimates are that 26 people currently possess as much wealth as the bottom half of all the humans on this planet—roughly 3.5 billion people (Boghosian, p. 72)—and to put that in perspective, that’s the equivalent of a single classroom of students having as much money and resources as all the human beings living in Africa, India, and China combined.

Moreover, as these mathematical models indicate, the only way to counteract this inevitable inequity is the deliberate and active redistribution of wealth from those who have to those who have not. Hence, the only way we will get equal access to high-quality education in Maryland (or anywhere else) is to pay for it, and the only way that happens is if some pay more because others cannot. In addition, the old “you-get-what-you-pay-for” cliché is a cliché for a reason, and it is important to remember that the alternative to making sure that everyone has equal rights to a high-quality education contains its own costs. In the case of schools, the documented drop in the quality of education described in my Introduction has led to a less skilled workforce and a decrease in creativity (see Chapter 9) that directly correlates with the steady decrease in entrepreneurship in this country over the past 40 years and the corresponding absence of new economic opportunity.

That might not matter if you’re one of the 26 and their peers. But if you are one of those 3.5 billion and their peers, that loss has been deeply felt, and if the morality of the situation doesn’t convince, then perhaps pragmatism will. The ghosts of Louis XVI, Marie Antionette, and Czar Nicolaus (as well as the memories of my students that day) can all too readily inform what really happens when the “have nots” get desperate. The planet earth is a finite place, and as the cheesy line from Disney’s High School Musical reminds us, we really are “all in this together.”

References

Boghosian, B. (2019) The Inescapable Casino. Scientific American, November. Pp. 70-77.

Brown, C.; Sargrad, S.; Benner, M. (2017) Hidden Money: the Outsized Role of Parent Contributions in School Finance. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/reports/2017/04/08/428484/hidden-money/.

Buchanan, L. (2015) American Entrepreneurship is Actually Vanishing. Here’s Why. INC, May. https://www.inc.com/magazine/201505/leigh-buchanan/the-vanishing-startups-in-decline.html.

Gaines, D. (2019) Maryland PARCC Results At A Glance: English Scores Up, Math Down. Maryland Matters. https://www.marylandmatters.org/2019/08/28/maryland-parcc-results-at-a-glance-english-scores-up-math-down/.

Maryland Association of Counties. (2019) Education Funding Per Student Charts for 2019. https://conduitstreet.mdcounties.org/2019/02/20/funding-per-pupil-charts-for-2019/https://conduitstreet.mdcounties.org/2019/02/20/funding-per-pupil-charts-for-2019/.

Maryland Public Schools. (2019) Maryland 2018-2019 Report Card. http://marylandpublicschools.org/stateboard/Documents/12032019/TabF-MarylandReportCard.pdf.

State of Maryland (2020) Maryland Commission on Innovation & Excellence in Education. http://dls.maryland.gov/pubs/prod/NoPblTabMtg/CmsnInnovEduc/2019-Interim-Report-of-the-Commission.pdf#page=11.