Education has become

the modern American caste system.

—Ted Dintersmith

What’s Missing?

With the mad dash to on-line learning to cope with the pandemic, some of my readers have asked my thoughts about this particular approach to education and whether I think it can be as effective as teaching in person. I have said elsewhere that I think teachers basically relate for a living, and therefore, like most in my profession, I am biased toward actually being with my students. Indeed, just the other day, the pain in the voices of teachers interviewed on NPR as they shared their feelings of loss was plainly evident, and with all the “social distancing” going on for so long right now, even the most introverted among us are recognizing the value of human contact.

However, merely missing our students does not in and of itself say anything about the educational value of on-line teaching and learning one way or the other, and therefore, I am going to suggest that we must ask two questions about this topic if we want to have a “meatier” understanding of the worth of the virtual classroom. First, I think we need to ask what is missing when we teach this way; second, I think we need to ask what is at risk when we teach this way. Let’s start with the former.

One thing that is potentially missing when moving education exclusively on-line is that for disciplines that rely heavily on collaboration (such as my own) it places some very practical limitations on what can be accomplished. Yes, yes; I know Zoom is everyone’s new best friend. But anyone who has worked in a small group knows that there is a synergy from the immediacy of the interaction that even technologies such as Zoom, Facetime, Google Duo, etc. cannot replace, and while anecdotal data at best, I have seen this firsthand even when watching a research team during my summer internship craft a shared Google Doc together. The ideas simply flow faster and more frequently.

Which is also part of the practical limitation on-line environments have. I have sat on enough distance meetings to know that the actual communication process itself takes longer (in part because technology’s current bandwidth simply makes the instantaneously in-person impossible), and thus, either a problem-solving process takes longer, leaving less time for the next problem, or fewer problems get tackled. The bottom line is that an exclusively virtual education places limits on productivity.

Furthermore, for disciplines that rely on direct physical interaction, on-line learning is effectively impossible. VR has made some pretty significant strides, but if you are a dance instructor right now, about all you can do is have your students practice individual technique. Choreography requires dancers, plural, together in the same room at the same time. Also, unless parents and guardians are available to follow their child’s elementary teacher’s instructions on how to do it, younger children are not learning how to read right now. Ask any experienced 1st and 2nd grade educator: there is no more hands-on intellectual activity in the world than learning to read.

Another significant aspect of in-person education that goes missing from on-line learning is the socialization process. As I mentioned briefly in Chapter 3, you are not born with the different parts of the brain communicating very effectively, and a significant role schooling plays in human society is to help teach the cerebrum how to control the limbic system. We need to do this because located within the more ancient limbic system parts of the brain is a structure known as the amygdala, which is responsible for what are known as the primary emotions: fear, anger, want, and lust. They are called the primary emotions because they are the first emotional response to anything and everything we experience. There is then a direct line of neurons between the amygdala and the hippocampus (discussed extensively in Chapter 3), and the latter uses these first emotional tags to judge whether the awareness of given situation is worthy of shipping off to long-term memory for future reference.

What’s more, if we look at that list of emotions, this process makes perfect sense from the perspective of evolution: each primary emotion is involved in the act of survival. We want to remember what to avoid, where to eat, and who to mate; if we don’t, we are not very likely to pass on our genes to the next generation.

But as instinctive responses, these are not very helpful in a society. Anyone who has worked with, been around, or raised toddlers knows that they bite and throw tantrums (fear and anger), take and don’t share (want), and can be prone to “playing doctor” (lust). We use the educational process (along with parenting) to teach the part of the brain that makes us fully human, the cerebrum, to control these responses and to—as parents and teacher alike like to say—“make smart choices.” Moreover, we need to do it all over when puberty floods the limbic system with hormones and signals it has never seen before, and the amygdala threatens to take control again. There is, after all, a reason for Mark Twain’s famous quote: “when I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much he had learned in seven years.”

This need to teach the cerebrum to control the limbic system, though, is only one component of the socialization process. As I have argued throughout this project, one of the fundamental things authentically engaged teachers do is serve as role models of what it means to be genuinely human, and that is rather challenging to do on-line. Our uses of technology already have us “struggling to maintain meaningful connection with each other” and in full “relational retreat” (Turkle, pp. 6 &154). Moving teaching and learning exclusively on-line simply exacerbates this situation. It places electronic barriers to the communal character that I have argued is the very heart of the teaching and learning process, and thus on-line learning can never adequately replace what happens in a brick-and-mortar classroom (see Chapter 9 for more about the impact of technology on education).

The bottom line is that teaching is fundamentally about loving, and we cannot love in the same way through a wi-fi connection. I think as a society we once kidded ourselves that we could. But all of us currently experiencing the enforced distance from our extended families due to COVID-19 understand now—more deeply now than we ever have before—how video chatting is just not the same as in-person contact. It can help, but it is not entirely adequate. In fact, as Sherry Turkle observed in a recent NPR interview, the isolation from the coronavirus pandemic may finally be getting people to see what has been truly missing from our always-on-our-devices world.

Speaking of missing, the last thing I think we lose when we move exclusively to on-line educating is some of the motivation needed to stay on-task during the learning process. Not everything we study in order to become functional adults is intrinsically exciting or interesting, and not every subject is a given child’s, tween’s, or adolescent’s intellectual passion. Hence, staying on-task on-line when simply being on-line itself presents a nearly infinite world of possible distractions is likely to challenge the resolve of even our most dedicated students. Younger children especially can have difficulty focusing even when a teacher is physically present with them, and with a parent or guardian perhaps needing to telecommute in the next room, the absence of the practical supervision that in-person education provides cannot help but have an adverse impact on both the quantity and quality of learning taking place.

What’s at Risk?

In addition to limiting the amount and type of content that can be taught when the entire educational process moves on-line, there are also some negative things I think we actively risk happening when we do so. One of them is that it can be all too easy to fall back on lecturing and other passive reception models when using this vehicle to provide content. As discussed in Chapter 3, the employment of such methods is effectively bad brain science as these types of engagement with content do not lead to successful memory retention, and as examined in Chapter 4 and 5, the less students are actively “doing” a particular discipline, the less learning is actually taking place. That is why, for example, teaching children to read on-line is so nearly impossible; you need someone sitting down with the child with a book, pointing at words together, using phonetics, etc. to make it happen. Simply listening to a teacher read a story on Zoom as the students follow along with their own copy doesn’t get the job done, just as watching a cooking show does not create the conditions to learn how to cook!

Furthermore, a related risk that happens with virtual learning is that it is too easy to equate training with teaching. Granted, there has been a traditional distinction between these two processes that says training is something we do with skills while teaching is about knowledge. But I don’t think this distinction gets to the true difference between the two processes. I think training is fundamentally passive in character while teaching is fundamentally active, and here’s why: when I was in high school, I worked for MacDonald’s, and on the first day on the job, I was taken to a room and shown a video tape of how to run the fryer. I then spent the next several work shifts doing what I had been shown. Running the fryer was a skill I was shown and then did. But when I was even younger, I learned a very different skill, reading, and yet no one would ever say that I was trained to read. We would say that I was taught to read, and we would do so because learning to read required a dynamic back-and-forth engagement between myself and my teachers for me to master this skill.

Hence, I would argue that what distinguishes training from teaching is not the nature of the content or material but the mode of transition. That is why I am concerned that educating in the virtual realm risks conflating the two. When doing on-line teaching, it is far too easy simply to show something and think that learning has happened—to train when one thinks they are teaching—and it is yet another reason why lecturing is among the least effective pedagogical methods: it is basically verbal showing.

However, all these potential risks to the pedagogy of teaching pale in comparison to the real risk the move to exclusive on-line learning will actually have on far too many of our children: the digital divide. Depending on which FCC data examined, somewhere between 19 and 21.3 million individuals in this country currently have no access at all to any fixed broadband internet connection (defined by the FCC as a link with at least a 25Mps Download—3 Mbps Upload processing speed). These are people who literally cannot get on-line at all because the hardware for doing so is simply not in place, and most of them live in our rural areas (14.5 to 18.8 million). This data does not include the effectively 99% of Americans who have mobile access through smartphone technologies with at least the minimum speed of 5Mps/1Mbps, but because many available mobile speeds are not adequate for the kind of information processing needed for even adequate on-line learning, this leaves millions of children effectively shut out of school as they are required with their families to shelter in place during the current pandemic.

Furthermore, there is rural and there is rural. In Maryland and Connecticut, for example, 94.8% and 99.5% of their respective rural citizens have access to fixed broadband internet; whereas only 48.7% on average of those living in rural Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming have access. Therefore, where a child lives right now directly impacts that child’s likelihood of moving successfully to the on-line learning the COVID-19 virus is necessitating, and because that will impact the quality and quantity of their educational experience for the foreseeable future, already existing inequities between urban and rural parts of our society will simply grow ever larger.

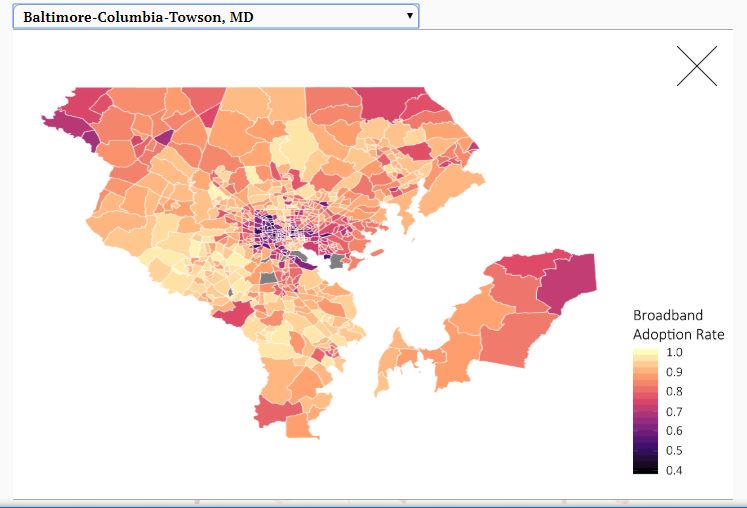

Yet there is an even larger group of Americans that are on the wrong side of the digital divide because of economic disparities, not just an absence of technological infrastructure. According to the Brookings Institute, there were 18 million households in 2018 (an estimated 100 million people; roughly a third of our population!) without the ability to afford the broadband subscription necessary for on-line education. What is more, hidden within those numbers is a little examined issue, and that is that the majority of these digitally disconnected households are located not in rural areas but in our urban metros. Thus, 13.9 million of those 18 million households live in cities and their surroundings, and as was true with the rural data, it also matters where you live geographically, with eight of the metropolitan areas with the highest rates of digital poverty (20% of their total populations) located in the Southeast. Indeed, if we examine the data for Maryland (see map), it will not shock any of us living here to see where the highest concentration of these zones of digital poverty are. Nor, shamefully, what most likely is the color of the skin of the people living in them.

The simple reality is that there are entire populations of our students throughout the United States for whom a need to move entirely to on-line learning is at the very best problematic, and that’s before confronting the fact that many of these same children also do not even have access to the actual devices needed to do it in the first place. The data on this additional disparity is too anecdotal to make statistical claims, but that doesn’t make its impact any less real or keep it from making the digital divide even worse. Therefore, the disparities of the digital divide are even greater than I am fully able to describe, and so too, then, is the risk it presents during the current situation of increasing the injustices and systemic racism it already helps to perpetuate.

What’s more, the students struggling with the digital divide are not the only marginalized children at risk in the all-on-line learning situation. Those with learning disabilities, those who fall along the autism spectrum, those for whom English is a second language—all need levels of extra support not easily provided over the internet. In addition, there are all the homeless kids and other children living with the threat of violence, neglect, and/or abuse for whom daily schooling often provides the only safe space in their lives. Thus, perhaps the biggest risk of all to the abrupt move to on-line learning forced on so many of us by the COVID-19 virus is that every child in our society who was already at an educational disadvantage is likely to fall even further behind in terms of learning, simply compounding already challenging socio-economic issues.

It’s not a pretty picture, and I simply pray that there are enough caring adults out there in the lives of all our children to help them make it to the other side as undamaged as possible. Stay safe; stay well!

References

FCC (n.d.) Eighth Broadband Progress Report https://www.fcc.gov/reports-research/reports/broadband-progress-reports/eighth-broadband-progress-report

FCC (2019) Broadband Deployment Report https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-19-44A1.pdf

Fishbane, L. and Tomer, A. (Feb. 6, 2020) Neighborhood Broadband Data Makes It Clear: We Need an Agenda to Fight Digital Poverty. The Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/02/05/neighborhood-broadband-data-makes-it-clear-we-need-an-agenda-to-fight-digital-poverty/

NPR Morning Edition (April 3, 2020) K-12 Schools Try To Salvage The Term By Teaching Remotely, April 3. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/03/826522327/k-12-schools-try-to-salvage-the-term-by-teaching-remotely?utm_medium=RSS&utm_campaign=morningedition.

NPR On-Point (April 1, 2020). Staying Connected, Virtually: What We Lose Online. https://www.npr.org/podcasts/510053/on-point

Turkle, S. (2017) Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, 3rd Edition. New York: Basic Books.

In response to your blog on online learning, I offer the following. Recently, I had an opportunity to speak with three families of sixth graders in public schools in Maryland and received both disparate and somewhat surprising responses. The first case involves a student who’s mother is a high school English teacher. He is naturally motivated and his mother is home to provide guidance and he is doing well. Secondly, a neighbor student who already has learning challenges, is basically receiving no parental oversight. Given a choice to do her online learning or play non stop video games, she has chosen the latter. In the third case, a good student in a school in the best county in Maryland is also excelling at home with learning. She is doing so well, the parent has decided that she will not return to the classroom in lieu of home schooling going forward.

LikeLike