If you were to poll people today about the greatest challenge facing not just this country but humanity itself, the list of logical candidates that come immediately to mind might include the pandemic (duh!), the climate crisis (another no-brainer), and the authoritarian threats to democracy (including numerous state republican legislatures here at home). However, I would argue that an even greater challenge we face today is misinformation (and its manipulative cousin, disinformation), and I am not alone in this conviction. The World Health Organization has actually called the attack on empirical truth today in various media and on-line venues an “infodemic,” and in one of my favorite political cartoons of the past year (for which I can only provide a link due to copyright), Bill Bramhill of the New York Daily News has the traditional Four Horsemen—War, Famine, Pestilence, & Death—joined by a fifth called “Misinformation,” riding right along beside them, head buried in a cellphone.

Yet, psychologists who study and research the phenomenon of “fake news” point out that probably the greatest challenge facing us is neither the misinformation nor disinformation itself but rather the very nature of how our brains process information in the first place. The science shows that we are all susceptible to what Sander van der Linden of the University of Cambridge calls “the six degrees of manipulation”—impersonation, conspiracy, emotion, polarization, discrediting, and trolling—because anytime we hear something, we instinctively process it through our pre-existing biases, employing what is known as “selective skepticism” to filter our attention. Indeed, so potent and hard-wired is this confirmation bias, that even when we later hear a correction that we deliberately choose to accept as valid, our thinking and decision making will still operate employing the original message. In other words, we will regularly behave subconsciously out of the original bias even when we have rationally embraced that it is false or wrong.

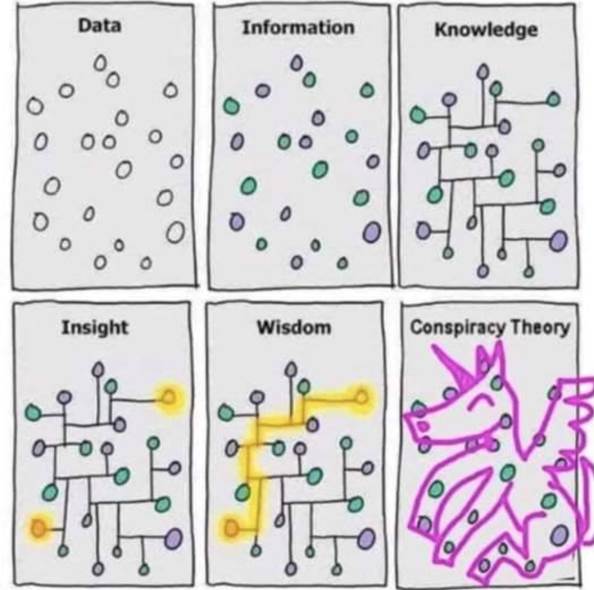

What this all means for lucid reasoning is sobering. Our tendency in education is to assume that if we can just convince people to fact check enough or teach individuals how to discern legitimate sources of information from spurious ones, then rational thought and empirical truth will prevail—that we can persuade hesitant individuals to vaccinate and mask up; that we can convince climate change deniers of our mutual peril; that we can make the right to vote equally accessible to all. We want to believe that the data will prevail and that people can indeed recognize when the emperor truly is naked.

Yet our pesky brain seems to be standing in the way of everyone (or maybe anyone!) achieving authentic insight, and to get some idea of just how easy it can be do go down the proverbial rabbit hole of misinformation and disinformation, I recommend exploring an on-line activity developed by van der Linden and his colleague, Jon Roozenbeek, called Go Viral! Especially for those of us who do not spend our days on TikTok, Yik Yak, and Instagram (avoid them even!), this plunge into the world of social media and its role in van der Linden’s “six degrees of manipulation” is quite revelatory as to the power of these technologies to shape how we experience and interact with others in the world. If you have never experienced the power of “likes,” the dopamine hits that come with them, and the ugly choices one might make to keep them coming, then this on-line game can be positively eye-opening.

What are we to do, then, if even our own brains seem against us? How do we successfully fight misinformation and disinformation in ourselves—let alone society at large? It can feel like a futile battle, and anyone who has seen the recent Netflix satire, Don’t Look Up, about an extinction-level sized comet hurtling toward the earth knows exactly what I’m talking about when I say it seems as if a just, harmonious, healthy society is simply no longer possible in the worldin which we live. As Stephan Lewandowsky of the University of Bristol points out, “even in the best of all possible worlds, correcting misinformation is not an easy task,” and “psychologists who study fake news warn that it’s an uphill battle, one that will ultimately require a global cooperative effort among researchers, governments, and social media platforms.”

However, perhaps all is not lost. That game van der Linden and Roozenbeek developed? It turns out that its purpose is to inoculate and immunize individuals against the power of “fake news,” and the research into its impact has shown that it boosts a person’s ability to identify and resist misinformation for a full two months after playing it. What’s more, if all the adults in children’s lives would start taking their stewardship of the future seriously, we would not even have need for such a game in the first place.

What do I mean by that? I mean reading a book to your toddler instead of shoving a screen in front of their face to occupy them. I mean denying smartphone technologies to those too young to know how to use them appropriately because otherwise we are doing the equivalent of giving guns and alcohol to our children and expecting their undeveloped prefrontal cortices to make smart choices. I mean contacting your legislator and demanding social media reform, and if you are a legislator, having the guts to standup to a monopoly that threatens the very fabric of our society. I mean getting off our own devices and living in the immediate now: experience boredom and the creativity it engenders, examine the quality of one’s thoughts, touch another’s life with your actively focused attention.

As for educators, I’m afraid we do indeed have our work cut out for us. We have to be willing to collect every cellphone in the room at the start of every class. We have to be willing to immediately but kindly drop whatever is happening in a lesson to address a falsehood the moment it pops up in class just as we would a micro-aggression. We have to teach media literacy in the context of our subject matter even if doing so means we don’t get the Krebs Cycle or the 30 Years War covered. Most importantly, we have to model the embracement of empirical truth in our own behaviors if we are to expect and encourage our students to do the same.

Anything less on the part of all of us who are adults, and our children are not going to get the future they deserve.

References

Abrams, Z. (March 1, 2021) Controlling the Spread of Misinformation. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/03/controlling-misinformation.

Committee on Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs. (Oct. 28, 2021) Social Media Platforms and the Amplification of Domestic Extremism & Other Harmful Content (Full Committee Hearing). The United States Senate. https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/hearings/social-media-platforms-and-the-amplification-of-domestic-extremism-and-other-harmful-content.

Staff (March 28, 2019) Reading to your toddler? Print books are better than digital ones. Michigan IT. https://michigan.it.umich.edu/news/2019/03/28/reading-to-your-toddler-print-books-are-better-than-digital-ones/.