A time to weep and a time to laugh,

A time to mourn and a time to dance.

—Ecclesiastes 3:4

The human disease is often painful,

but it’s only unbearable

for as long as you’re under the impression

that there might be a cure.

—Charlotte Joko Beck

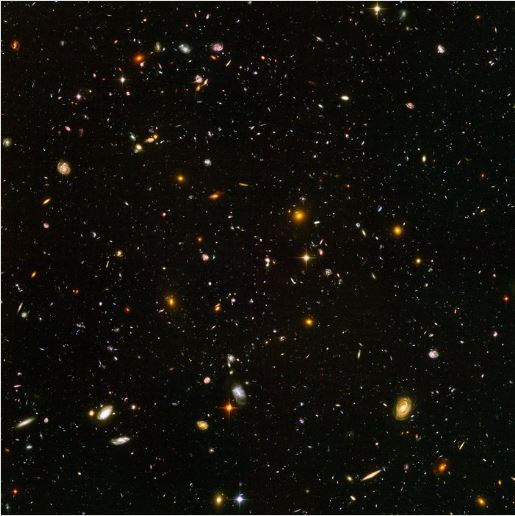

Many years ago, the school I was then at had the privilege of having noted astrophysicist, Mario Livio—he of Hubble Telescope fame—come and address the entire Upper School about his work at the Space Telescope Institute at Johns Hopkins University. His address was about the many wonders Hubble had revealed about the nature of the universe, and on one of his slides, he displayed this image:

He explained that this is what is known as an ultra-deep field image and that the points of light that look like individual stars are in reality entire galaxies, each containing hundreds of millions, if not billions, of individual stars. He then when on to share that the image we were looking at represented only 1 degree of the night sky, and that if we were to rotate the telescope through a full 360 degrees—and he slowly, deliberately turned his body through an entire rotation to emphasize his point—we would observe that what is in that image would be observed in every single degree. What’s more, he punctuated, that was with rotating the space telescope along only one axis! In short, he summed up, “we live in a universe of uncountable numbers of stars with uncountable numbers of worlds, each its own potential haven for life.”

The audience was spellbound, and the Q&A that followed, lively. But what I remember most about that day was later in the afternoon, as my AP biology students filtered into the room, I asked them what they had thought about Dr. Livio’s lecture, and Serene Mirza replied, staring at me with this look of total bewilderment:

He was awesome, Mr. Brock. But I have to confess, hearing him and seeing that image…well, it made me wonder: Why we are even bothering having class today? What’s the point of studying any of the stuff we’ve been learning? If the universe is that vast, can anything be relevant? Can any of us be relevant?

The short answer to her question, of course, is “no.” My student was totally correct in her observation, and as journalist, Oliver Burkeman puts it, “it’s useful to begin this stage of our journey [about time] with a blunt but unexpectedly liberating truth: that what you do with your life doesn’t matter all that much—and when it comes to how you’re using your finite time, the universe absolutely could not care less” (p. 208).1 The basic truth is that at a fundamental level, all any of us are are consumers of food and oxygen and producers of urine and carbon dioxide—just like every other vertebrate on the planet. Indeed, as I start the year with my Advanced Biology class, I point out that we are even more basic than that; that we basically consist of electrons transiting from one atomic orbital to another.

And if you think of all the countless humans who have consumed their food and oxygen and produced their urine and carbon dioxide, who have had their electrons transit and then left no trace of themselves whatsoever…well, you get the idea. We have zero cosmic significance as a species, let alone as individual members of that species.

Yet there seems to be this deeply rooted psychological urge, bordering on biological need, to believe that what we do with our discrete unique lives should somehow matter, should make a significant difference in the proverbial grand scheme of things, and in fact, there is a term in psychology for this belief: egocentricity bias. What’s more, when we think about it from an evolutionary standpoint, this bias makes perfectly good sense because if each of us had a genuine sense of our own irrelevance, we might not struggle as hard to survive and reproduce. We need to think highly of ourselves in order to propagate the species.

It is also true that it is not a certainty easy to swallow. As essayist Katherine May points out:

Some ideas are too big to take in once, and completely. Believing in the [irrelevance] of my place on earth—radically and deeply accepting it to be true—is something I can do only in fits and starts. It is in itself an exercise in mindfulness. I remind myself of its force, but the belief soon seeps away. I remind myself again. It drifts off with the tide. This does nothing to diminish the power of the next realization, and the next. I am willing to do it over and over again, throughout my life. I am willing to accept it may never actually stick (p. 234).

Yet there is a value to it sticking, even if only a little, because “to remember how little you matter, on a cosmic scale, can feel like putting down a heavy burden that most of use didn’t realize we were carrying in the first place” (p. 210). When you let go of the idea that you must somehow make your life matter, “you’re freed to consider the possibility that many of the things you’re already doing with [your life] are more meaningful than you’d supposed—and that until now, you’d subconsciously been devaluing them, on the grounds that they weren’t ‘significant’ enough” (p. 212; original emphasis). Thus:

From this new perspective, it becomes possible to see that preparing nutritious meals for your children might matter as much as anything could ever matter, even if you won’t be winning any cooking awards [and] that virtually any career might be a worthwhile way to spend a working life, if it makes things slightly better for those it serves (p. 213).

The truth is that the majority of us live modestly meaningful lives and that even those who make it into the pages of our history live, at best, slightly more significant ones. Think about it. Our knowledge of the Pharaohs of Egypt or the Mayan Kings or the Xia Dynasty is already extremely limited, and 10,000 years from now even that little will most probably have faded into oblivion. And in as little on the cosmic scale as a million years from now…?! As the poet, Shelley, once wisely wrote:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

However, there is one way in which every single human who lives, has ever lived, and ever will live has deeply meaningful and lasting significance, and here is where the educator in me stirs. As I teach my seniors, every single one of us participates in an intricate web of ecological—as well as sociological—relationships, each of us a nexus point, and every single action we take as individuals generates waves that ripple out throughout that web.

The food you eat and the soap you bathe with? They determine the microbial populations that inhabit your body, which in turn contribute to the quality of your health…. Where you purchase those and other items? It impacts the livelihoods of those in the supply chain, which in turn contributes to the stability of your neighborhood…. How often you drive? That governs the amount of carbon dioxide you contribute to a changing climate, which in turn alters the weather you experience as it manipulates the jet stream….

I could clearly go on indefinitely, but that is why I always end the school year with my seniors the same way. Throughout the year, they have had to write “Issues in Science” essays about how some of the biological ideas we have studied have the potential to impact society at large (e.g. since energy transformation in living systems never stops, how do we define death?2) and so after our last unit of the year—the environmental science one where I have to teach them just how badly humans have screwed the planet up—I inform them on the very last day of class that I am assigning them their final “Issues in Science” topic.

My speech pretty much goes like this:

Today, I am assigning you your last Issues in Science paper—pause to allow for the looks of shock, consternation, and anger to appear on their faces—Relax, you’re not writing this paper for me. No, this is an essay you are going to write with your lives—with the decisions you make and the actions you take—I’m just the messenger making you aware of the topic for it. And I won’t be grading this essay; the universe will. A universe which, as we have learned this year, grades on one scale and one scale only: pass/fail. What’s more, if you think I’ve been a demanding grader!—pause to let that one sink in; there are some chuckles and knowing smiles—You are now among some of the most knowledgeable people on the planet, and knowledge as we know is power, which makes you among some of the most powerful people on the planet as well. Hence, your final Issues topic is this: What will you do with your power?

Or as I may now have to phrase it: What will you do with your modestly meaningful life?

To which, all of us, I would ask the same.

If you’re reading this, you know what I’ve done so far with mine.

1Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes are from Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks.

2Read Carl Zimmer’s Life’s Edge if you want to see just how challenging defining life or death truly is; the legal definition alone has changed more than once in my lifetime.

Author’s Note: “A Modestly Meaningful Life” is the last in my series on time and education. Be sure to check out: “The Clock Is Always Ticking…,” “Managing ‘Now’,” and “A Time for Every Purpose.”

References

Burkeman, O. (2021) Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. May, K. (2020) Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times. New York: Riverhead Books.

This time your wise words moved me to find my old paper from AP Bio at RPCS entitled “ What will I do with my power?” While I am not the writer that you are, I was moved by both my words and your comments. I realize that it is clear that my ability to write about what I would do with my power was the direct result of your inspirational teaching.

By the way,I have loved reading this series, and just like a good Netflix show, it was sad to come to the end of the last episode.

Debby

LikeLike