The complexity of our society owes its existence

to the multiple improvements

that education brings to our cortex.

—Stanislas Dehaene

The United States is now a country obsessed

with the worship of its own ignorance.

—Tom Nichols

Anyone who has read my Introduction or followed the LaC Updates knows that I believe one of the fundamental pillars for a teacher’s authentic engagement in the classroom is a thorough grasp of what the neuroscience reveals about how human brains function. Chapter 3, in fact, is devoted to what I consider the minimal knowledge about the brain that even the most novice educator should possess before working with children. However, during my summer hiatus since my last posting in June, I have been deliberately catching up on the latest cognitive research, and what I have newly learned has profound implications not only for the teaching and learning process but for the current state of education in our society as well. Hence, I invite all my readers to join me for this update on the brain and, if you are a fellow educator, to share out this information as well.

The Myth of Tabula Rasa

From previous studies (see Medina, Gazzaley/Rosen, & Seth), we already know that our immediate awareness is a projected mental model of the world generated by the brain—a “controlled hallucination”—which is tested against the data from the sensory inputs to determine its veracity. Our brains accomplish this task through evolutionarily pre-selected algorithms employed in the various sensory cortices, and the consequence is that our immediate awareness is always living slightly in the future, “fantasizing” what the world around us might be like, constantly double-checking to see if we are correct.

However, for the longest time, there has been a working assumption that any changes in the quality or character of this “fantasizing” (i.e. learning) was due exclusively to the input received from the environment—that the brain was a “blank slate” onto which the senses composed our knowledge (e.g. how to distinguish one face from another). Experiments by noted Swiss psychologist, Jean Piaget, and those who followed seemed to affirm this assumption, and within the limits of their tools and methodologies, these researchers made valid conclusions from their evidence.

But science is a process, and with the fMRI scans and other techniques available today, we now know that any understanding of the brain as a tabula rasa is a total myth. In fact, what the most recent research has revealed is that evolution has pre-loaded our brains with certain algorithms (and the parts of the cortices to process them) for modeling the world such that the brain “always starts with a set of a priori hypotheses, which are projected onto the incoming data, and from which the system selects those that are best suited to the current environment” (Dehaene, p. 26).

Among these pre-loaded algorithms are the concept of objects, a sense of number, intuitions about probabilities, knowledge of animal autonomy, language acquisition, and facial recognition, and with them, a newborn explores the world with certain innate understandings of it already in place—meaning that just as a baby does not need to learn to see (the visual cortex just does it), neither do they need to learn “that the world is made up of objects that move coherently, occupy space, do not vanish without reason, and cannot be in two different places at the same time” (Dehaene, p. 54). They simply employ this knowledge from birth to make accurate predictions about the objects in their immediate environment and then use this innate knowledge to learn ever more complex ideas about objects (such as what factors make an object fall or stay put).

Therefore, what the most current cognitive data on infants demonstrates is that:

we come into the world with a vast number of possible combinations of potential thoughts. This language of thought, endowed with abstract assumptions and grammar rules, is already in place prior to learning. It generates a vast realm of hypotheses to be put to the test [where] our brain must act like a scientist, collecting statistical data and using them to select the best-fitting generative model (Dehaene, p. 52).

It is an understanding of the brain that borders on Platonism, suggesting that “each human baby’s brain potentially contains all the languages of the world, all the objects, all the faces….” (Dehaene, p. 52)—everything it must ever know. However, “a vast realm” is not infinite, and what other recent research shows is that learning absent some constraints simply does not exist. All brain algorithms employ pre-loaded assumptions about what they are predicting, and our genes lay down the necessary brain architecture to guide our learning within these restrictions. In other words, in the same way the optical cortex and its algorithms limit what can be seen—because natural selection has ruled out predicting models about UV and Infrared wavelengths since there are no sensory inputs to test them against—so too, the brain’s pre-loaded knowledge algorithms place certain limits on what we can learn—again because “from evolution, we inherit a set of fundamental rules from which we will later select those that best represent the situations and concepts that we will have to learn in our lifetime” (Dehaene, p. 79).

Yet, there are limits and then there are limits, and here is where the brain’s known plasticity comes into play. Most of us when talking about education and learning are not talking about the kinds of learning an innate number sense is going to produce (e.g. counting). Instead, we’re talking about things like reading and history and science, etc.—cultural things—and when it comes to these, cognitive psychologist Stanislas Dehaene is worth quoting extensively because I could not summarize the findings better:

any cultural learning must rely on the [hijacking] of a preexisting neural architecture, whose properties it [repurposes]. Education must therefore fit within the inherent limits of our neural circuitry, by taking advantage of their diversity, as well as of the extended period of neural plasticity which is characteristic of our species.… According to this hypothesis, to educate oneself is to [repurpose] one’s existing brain circuits. Over the millennia, we have learned to make something new out of something old. Everything we learn at school reorients a preexisting neural circuit in a new direction. To read or calculate, children [repurpose] existing circuits that originally evolved for another use, but which, due to their plasticity, manage to adapt to a new cultural function (Dehaene, 121-122).1

Thus, for example, when we learn to compare the sizes of quantities, fMRI scans reveal that our brains grow additional neurons in the number detecting area of the cortex. Later, when we learn the Arabic numeral system (the 1, 2, 3…most of us are familiar with), a fraction of these neurons become exclusively dedicated for this purpose, only lighting up in the scans when we are manipulating these numerals. This pattern of repurposing our innate number detecting neurons continues such that “all of us, at any stage of the cultural construction of mathematics, from elementary school students to Fields Medal winners, continually refine the neural code of that specific brain circuit” (Dehaene, p. 127)—and only that specific brain circuit; without our brain’s pre-loaded innate number sense, mathematics as a field of knowledge would simply not exist.2

Timing is Everything

Something similar happens when we learn to read. However, here the fMRI brain scans and other research reveal the reality of the human brain’s evolutionary limits. We know from earlier neuroscience studies that the brain possesses not only plasticity but also preservation (see Chapter 3 for an overview), and what the recent work of Dehaene and others about reading has shown is that because of this balance, there are windows of time when the brain’s ability to reconfigure its neural networks are more open and windows of time when this process is less open. To understand the how and why, let’s explore what happens in the brain as a person learns to read.

There are two innate brain abilities employed in the act of reading—language acquisition and facial recognition—and the way it works is that the group of neurons in the left occipital lobe of the visual cortex that evolved as the primary facial recognition circuit get repurposed to become what is essentially the brain’s letter repository. The language centers in the left hemisphere can then use this data to assemble word recognition and apply the necessary syntax rules (acquired from learning how to speak) to generate understanding. Thus, because we evolved to recognize faces and talk, we possess the necessary neural circuitry to hijack to invent writing and reading. Indeed, the better a person can read, the slightly slower they recognize faces as this processing gets shifted to the right side of the visual cortex; illiterates in fact respond more intensely to faces than literates do.

Which leads us back to the plasticity/preservation challenge. The longer an individual remains illiterate, the more the primary facial recognition neurons lock themselves into their original evolutionary purpose, making it harder and harder to repurpose them for reading. That is why grown adults who are trying to learn to read for the very first time struggle so hard at the task and why they never becoming truly proficient at it even when they are successful. Too much of those parts of their brains that could have been repurposed for reading have become preserved for other functions, limiting the plasticity available for performing the task.

Similarly, children with diagnosable reading difficulties also face a plasticity/preservation challenge. While the research into the “why” is on-going, brain scans of individuals with dyslexia or comparable conditions universally show reduced activity in the left occipital cortex when exposed to words. Something in these children is preventing their brains from repurposing the primary facial recognition circuit, and so interventions are needed to help their brains repurpose a different set of neurons before they can become successful readers—something which, again, must be done before these alternative (still unknown) neurons in the visual cortex get locked into some other purpose.

Hence, “the conclusion is simple: to profoundly [repurpose] our visual cortex and become excellent readers, we must take advantage of the period of maximum plasticity that early childhood offers” (Dehaene, p. 138). Moreover, we must do so because it is just not literacy versus illiteracy that is at stake. Someone who can read has almost double the short-term memory abilities of an adult who never attended school, and IQ increases several points for every additional year an individual’s degree of literacy improves. How the visual cortex gets repurposed impacts the entire brain’s capacity to learn.

Avoidable Disaster?

What is true for the visual cortex and its role in reading, though, is also going to be true of objects, probabilities, and all the other innate brain circuits. The bottom line is that learning brings multiple improvements to the entire cerebral cortex, and the implication for education of these most recent findings about innate algorithms and plasticity windows is obvious. The brain’s malleability versus conservation flexes in different cortical locations at different times as we mature (generally declining after full adulthood is reached). Therefore, those of us who are preK-12 teachers need to maximize the different optimum learning windows during childhood to establish the foundation and conditions for the ability for lifelong learning.

And nowhere is this truer than with those who teach our youngest children. Any delays in the development of literacy and numeracy during their prime window in early childhood can snowball quickly, and the poor reader who reaches my high school classroom is going to be put at significant disadvantage for learning the skills of abstraction and metacognition whose prime plasticity window is adolescence—which in turn puts the quality and capacity of that individual’s adult learning even further at risk than simply being semi-literate.

It also puts just about everything else in said person’s life at risk as well. I have already written extensively about how failures in learning contribute to the systemic racism and its consequent costs for individuals in this country (start with Equality vs. Equity), and I how looked extensively at how the pandemic is likely to exacerbate this failure even further (start with The Tally So Far). But it was not until I was recently reading Tom Nichols’ argument in The Death of Expertise that I began to consider the true enormity of the consequences if we fail to do what the neuroscience says to be doing in our educational systems.

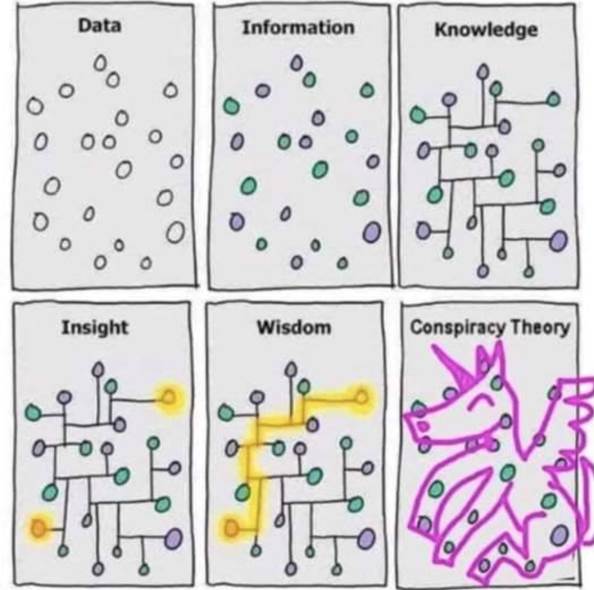

Nichols, a faculty member at the U.S. Naval War College and the Harvard Extension School, claims that “we live in an age of resolute narcissism…swaddled in a sense of sullen, unfulfilled entitlement that makes self-correction and continued learning almost impossible” (p. xvi). He argues that the typical American rejects the empirical rules of evidence, refusing to learn how to argue logically, and that consequently: “the foundational knowledge of the average American is now so low that it has crashed through the floor of ‘uninformed,’ passed ‘misinformed’ on the way down, and is now plummeting to ‘aggressively wrong.’ People don’t just believe dumb things; they actively resist further learning rather than let go of those beliefs” (pp. xx-xxi). This, he claims, not only puts at risk centuries of knowledge (antivaxxers anyone?) but undermines the very means to develop new understanding (such as how an individual’s behaviors contribute directly to climate change). Put it all together, he states, and “we court any number of avoidable disasters” (p. xviii), not least of which is the undermining and collapse of our Republic.

Now those who have read COVID-19, Climate Change, and Other Inconvenient Truths or Breaking Bad “Habits” will already know how fundamentally sympathetic I am to Nichols’ position. I am, in fact, one of those “others” he leaves it to to explain how we got to this “age of resolute narcissism” in the first place (see The Unprepared Generation). What’s more, I plan to take a deeper dive into Nichols’ ideas in a later post.

But currently, I want to place what he is arguing within the context of what the new brain research informs us about learning. First, if there are boundaries—however fuzzy—on the different windows of maximum plasticity for optimizing different types of learning, then there is an overall limited window for producing brains that can avoid the dangerous ignorance at work in our society today, and once a given individual is past this window, they now possess a brain either fully capable of productive lifelong learning or one that is actively preserving what I will euphemistic dub “ignorance” neurons in its various cortices.

Second, the overwhelming weight of evidence is that for at least the past four decades, most of the learning taking place in this country’s schools (public and private!) has failed to produce a critical mass of citizens who possess brains that are high functioning. See notes 1, 4, & 5 in the Introduction for references, but the data is clear that an overwhelmingly large number of brains leave America’s classrooms with their “ignorance” neurons firmly locked into place.

Third and finally, once the optimal windows of plasticity in a brain have closed, brains that have preserved their “ignorance” neurons run head long into the Dunning-Kruger Effect: the condition where those less skilled and less competent remain unaware of how unskilled and incompetent they truly are—or as the authors of the original study put it, “not only do [such individuals] reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it” (pp. 1121-1122).

What the neuroscience is showing us, then, is that poorly educated people possess brains that learn poorly as adults, that are limited in their capacity to change this fact, and that are not inclined to do so anyway. Or to put it wickedly bluntly, adults with “ignorance” neurons preserved and locked in are too stupid to know how stupid they really are. And they act accordingly.

Conclusion

The findings of neuroscience, then, would seem to help explain the very predicament Nichols contends we find ourselves in as a society, leaving a somewhat grim forecast for our future. But those same findings also explain why the other two pillars of authentic engagement in the classroom—appropriately intimate rapport and teacher as co-learner—generate the conditions for the kind of learning the does result in brain circuits shaped and preserved for productive lifelong success and thoughtful, engaged citizenry. By forming caring, trusting relationships with students and modelling for them what high-quality, successful learning looks like, teachers can optimize their impact during the brain’s years of maximum plasticity to produce the kinds of metacognitively aware thinkers our society and our world so desperately need. We need authentic engagement in our schools now more than ever.

Granted, that is easier to write than to do. In fact, reading the National Academy’s Call to Action for Science Education this summer, it was hard not to feel a pessimistic, almost defeatist sense of déjà vu as I thought “Thirty years, and we are still tasking educators with the same undone reforms.” When I add in my observations of the destructive damages of the pandemic and climate change, I will admit it: I am not very confident that whatever good there is of “the complexity of our society” will survive.

But as I remarked in My Deep Gladness, I seem constitutionally incapable of not “lighting candles against the darkness,” and if I ever need a reminder of the real potency of that light, it came in the form of an “ah ha” moment this past spring from my school’s graduation ceremony. One of my seniors, who was one of the commencement speakers, unexpectedly referenced me by name during her speech, and I found myself bewildered. Here I had just finished the worst year of my teaching career, under horrific conditions, at a brand-new school, and I learn that somehow, I had still managed to positively touch a child’s life. To say I was bemused and nonplussed is an understatement.

Not until I was walking home afterward, though, did the little proverbial mental lightbulb go off, and I suddenly realized not only why I work so hard to practice—however imperfectly—authentic engagement myself but why I do the same to promote it in others and address its absence in too many of our schools: as long as there is any real learning going on somewhere, sometime, there is hope, and where there is hope, there is a future worth fighting to sustain.

Therefore, as I start to prepare for my 34th Fall working in schools, you will find me once again with my students, learning right beside them, working to show them they are loved, and—as always—following the brain science…wherever it may lead.

1Author’s note: the original French term Dehaene uses in this passage is “recyclage,” which has slightly different connotations in French than it does in English. So I have replaced “recycle” with a term that better corresponds to his actual meaning, which is “repurpose.” I will use “repurpose” throughout the remainder of my discussion.

2Author’s note: as a strictly philosophical aside, the limitations created by the innate learning circuitries of the brain on the learning process has interesting potential consequences for our understanding of epistemology: if we can only know what the evolution of our brain’s architecture allows, then any organism with an alternative architecture (birds are a good example) could at least theoretically have knowledge that not only we do not have but cannot have because we do not possess the brain architecture to generate it. We literally could not know that we do not know.

References

Dehaene, S. (2020) How We Learn: Why Brains Learn Better Than Any Machine…for Now. New York: Penguin Books.

Gazzaley, A. & Rosen, L. (2016) The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kruger, J. & Dunning, D. (Dec. 1999) “Unskilled and Unaware of it: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments” in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6); pp. 1121-1134.

Medina, J. (2014) Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School. Seattle: Pear Press.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine. (2021) Call to Action for Science Education: Building Opportunity for the Future. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

Nichols, T. (2017) The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters. New York: Oxford University Press.

Piaget, J. & Inhelder, B. (1969) The Psychology of the Child. New York: Basic Books.

Seth, A. (Sept. 2019) “Our Inner Universes.” Scientific American; pp. 40-47.