My original title for this essay was “the future of education.” But if you’ll stay with me, you’ll see why I ultimately decided on the ellipsis, and why the potential future of education (at least in this country) led me to that choice. It has to do with the fact that there are some serious challenges to teaching and learning in the United States right now (as well as significant chunks of the rest of the world) that have caught my recent attention and that have me pondering the future of all manner of educational practice moving forward. Hence, it was time to take up my metaphorical pen and paper again to share my musings—as always in the act of hope that some might find them adding at least a degree of value to their own reflecting.

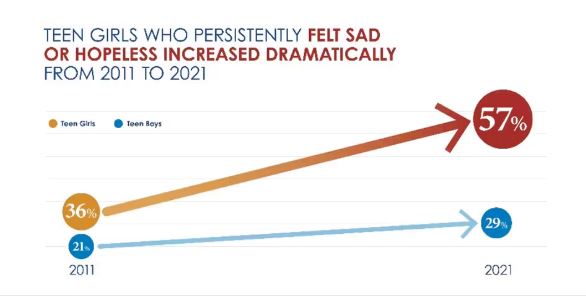

One of these challenges, of course, is the now ubiquitous one of digital technologies and their latest AI variants, and because I have already written so much on this particular topic, I simply invite anyone interested to visit my archive for those essays. Today, my only addition to this subject is to share that while Australia had the courage to pass a law banning access to social media to anyone under the age of 16 over a year ago, it has taken my school nearly a year and a half of sometimes fierce debate among the faculty about well-researched brain science simply to finally collect students’ cellphones during the academic day. American individualism at its finest!

No, the two challenges catching my interest in the past month both involve the intersection of demography and child development, and the first of these has to do with plummeting birthrates in much of the world’s developed economies. Here in the U.S., for example, the number of babies being born annually has dropped below the replacement level of 2.1 children per couple, and while the environmentalist in me sings hosanna for the planet’s sake, the educator in me who lives in a capitalist economy recognizes the threat this poses to schools across the land. In Maryland alone, the loss of more than 11,000 children from the public schools this academic year (an estimate that nearly tripled during the week it took to write this) has endangered funding in several of our counties, and the competition among the area private schools risks becoming cut-throat as institutions with sometimes literal centuries of existence struggle for butts in chairs. Already, three such schools in my immediate area have shut their doors in the past five years, and even a Baltimore City public charter school with a 30-year storied history just announced its closure.

Those are all lost jobs—as well as lost professional experience and wisdom—and the impact is likely only to exacerbate the teacher shortage already facing this country as the economic uncertainty confronting anyone thinking of entering the profession continues to grow. However, for me, the saddest truth about these school closures is that they are lost opportunities for certain children to find their safe and successful learning “niche.” My niece was never able to find hers, and it almost cost her her life; so I know firsthand how important the quality of a learning environment can be. Shuttered and silenced classrooms leave gaping holes in any community, and in the coming decades, what is happening today will only be the beginning. As Marguerite Roza, the director of Edunomics at Georgetown University puts it, “cratering birthrates will seriously remake education in the country”—and unlikely for the better.

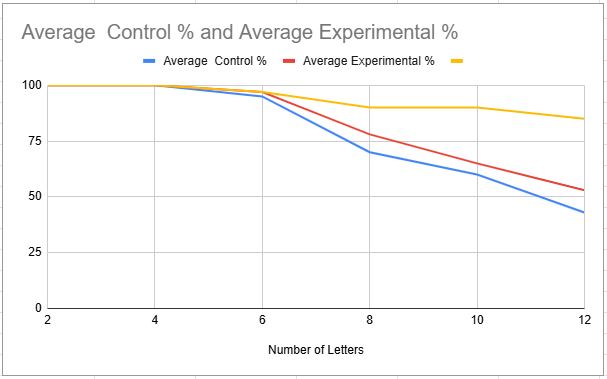

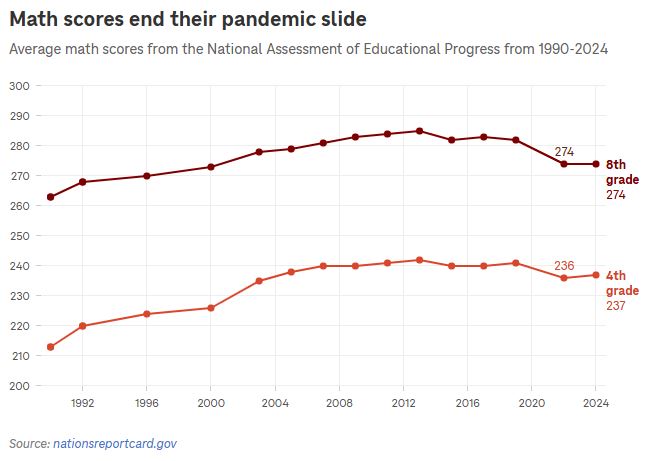

But there is perhaps an even more insidious challenge presented by the contemporary link between demography and child development, and that is the impact of the current cost of early childhood education in this country. Pre-K schooling for even a single child costs the typical family more than they pay for monthly rent in 17 of the 50 states, and nationwide, more than 60% of families cannot afford the kind of high-quality daycare so critical to developing brains. We know now that age 0 to 5 is the most important stage of growth for the human brain—with impacts that last for the entirety of an individual’s lifespan—and we know equally well that maximizing this growth requires well-trained, highly attentive adults guiding the process, with more than just one or two such adults present (the “takes a village” cliché has some literal truth). Furthermore, without this level of investment of adults in infants’ and toddlers’ lives, the quality of all future learning is compromised, and there is a direct correlation between a country’s investment in early childhood education and the PISA scores (the world’s gold-standard for testing academic progress) of their high school-aged children.

Yet if so much is at stake, why would our country not invest significantly in providing superior pre-K education—especially given the potential long-term economic benefits vs. economic costs? Part of the answer has to do with how our society has historically sought to use markets as the solution to so many of our social problems. Economies of scale and technological innovation have lifted much of the world—and especially us—out of poverty and material want; so why wouldn’t they—the thinking goes—be able to solve any seemingly intractable problem?

However, you can’t increase productivity in the interactions between an adult and a 2-year old (the genetic limitations of both their respective attention-spans preclude it), and you can’t innovate a way to make a small child any less of a time-suck. Hence, as Senior Fellow at the think tank Capita, Elliot Haspel, points out: the bottom line is that market forces are incapable of solving the need for well-trained, well-compensated adults “caring for and shepherding the brain development of [our] very young children.”

What’s more, he argues:

that market failure makes childcare essentially a hot potato. No one has any incentive to do that work, and everyone has an incentive to dump that work downstream onto others who are more vulnerable than they are — from policymakers onto families, from fathers onto mothers in many cases, and not even just to mothers, but from mothers in more privileged positions onto paid care providers.

Simply put, no one wants to acknowledge that small children are expensive, demanding, and inconvenient and that all the proverbial “king’s horses” and all “the king’s men” can’t make this reality be otherwise. Thus, we find ourselves today with either brain-drained, exhausted mother’s forced to stay at home (which the data is clear is not optimal for brain development either; again “the village”) or with families who already need two incomes to meet basic needs having to compromise those needs to pay for the childcare the second salary demands.

Which actually circles us back to the “cratering birthrates” as more and more adults are now deliberately opting out of having children simply because they cannot see how they can afford them.

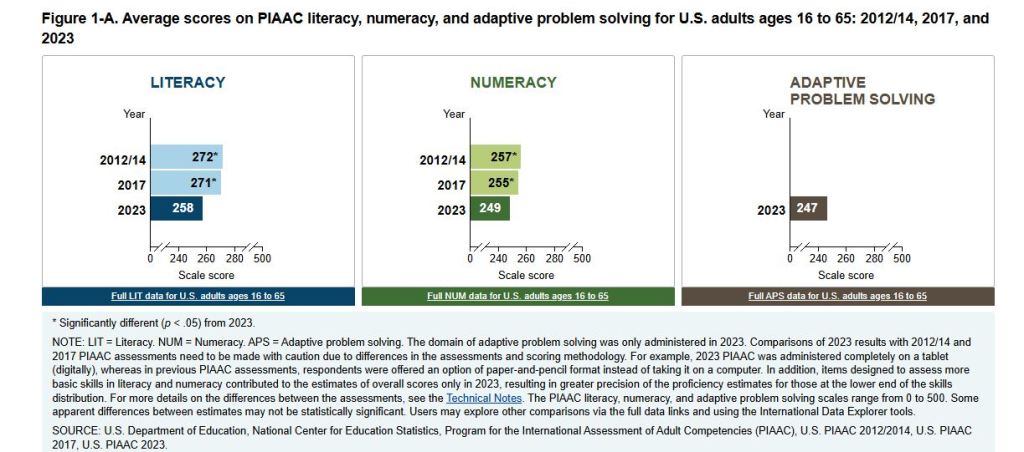

Interestingly enough, our country once did provide nearly universal daycare for our smallest children. During World War II, the need for women in the nation’s factories drove congress to pay for daycare centers across the country that cost those families the equivalent of $10 per day in today’s money (imagine only $3700 a year for childcare!), and staffing was not an issue because it was considered one’s patriotic duty to contribute to the cause. However, once the war ended, the patriarchy reasserted itself, and so we find ourselves in the mess we have today, with parents of all varieties mortgaging their economic futures just to have families and American society enduring the largest collective drop in intelligence since the 6th and 7th Centuries in Western Europe.[i]

It is challenging time to be a toddler in the United States.

And that’s the reality that compelled this latest round of writing and why I am pretty confident that anyone reading this can figure out the reason for my original working title. However, to connect the dots explicitly: fewer children in schools is likely to lead to even less investment in education (both human and capital); less investment is likely to lead to lower and poorer quality education; and that is likely to lead to pre-K teaching and learning—if there even is any—that fails to adequately develop little brains to their optimal capabilities. We are obviously still going to educate our children, but the character of that education and its results may not be what our society needs to thrive…or maybe even survive.

Hence, the ellipsis in my title. The future of education isn’t just about what goes on in classrooms and schools, and it isn’t simply about what I and many others do for a living. It is about the nature of the act of learning itself, and that means the future of education is the future of everything human. What we learn as children—every concept, every skill, every thought—is the entire foundation of our adult lives, and as the author of the Gospel of Matthew wisely had Jesus say, that foundation can be one of rock or of sand. Right now, I sense we are at a great tipping point in this country (and perhaps this world) where we still have the power to build on rock instead of sand. But we are dangerously close to defaulting to the latter, and should that happen, then the author of Matthew is quite clear about the consequence:

The rain fell, and the floods came,

and the winds blew and beat against that house,

and it fell—and great was its fall!

—Matthew 7:27 (NRSV)

[i] As a total sidebar, I find it intriguing that in the era from 1965 to 2005, the productive adult brains of those war era babies with their subsidized daycare produced some of the most robust R&D, discoveries, and inventions in all of human history. Hmm! Coincidence? Correlation? Or causation? You decide.

References

Bowie, L. (Nov. 24, 2025) Maryland Schools Lost Students This Year, Early Estimates Show. What’s to Blame? The Baltimore Banner. https://www.thebanner.com/education/k-12-schools/maryland-schools-enrollment-declines-C6FWKKHNYZH4DNJWAUOM4KLDGE/.

Griffith, K. & Richman, T. (Dec. 9, 2025) Maryland Public Schools Lost Over 11,000 Student This Year. The Baltimore Banner. https://www.thebanner.com/education/k-12-schools/maryland-public-schools-enrollment-drops-I7FPW6AIAJGNFDXFQDBMNMLME4/.

Kahloon, I. (Oct. 14, 2025) America is Sliding Toward illiteracy. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2025/10/education-decline-low-expectations/684526/.

Kukolja, K. (Nov. 29, 2024) Australia Passes Strict New Social Media Bans for Children. NPR All Things Considered. https://www.npr.org/2024/11/29/nx-s1-5210405/australia-passes-strict-new-social-media-bans-for-children.

Lora, M. (Dec. 5, 2025) How a West Baltimore Charter School’s 30-year Legacy Collapsed in Months. The Baltimore Banner. https://www.thebanner.com/education/k-12-schools/new-song-academy-closed-charter-school-baltimore-NIBASIGPAZA6HJKTS3JDH2BSCU/.

Luse, B; et al (Nov. 24, 2025) Kids are Expensive. Do They Have to Be? NPR It’s Been a Minute. https://www.npr.org/2025/11/24/nx-s1-5617226/kids-are-expensive-do-they-have-to-be.