priv◦i◦lege (priv⸍’l) n.—a special right or immunity granted or available

only to a particular person or group; an unearned advantage

In my own highly imperfect way, I try each day to remind myself what my white, male, cisgender, heterosexual privilege “buys” me in our society—to recall how blessed I am to have my health, work that I love, and the economic stability to spend my evenings watching Netflix. However, recently, I have had a couple of experiences that have caused me to view both my own individual privilege as well as the general inequitable distribution of it in our society in a whole new way, and the insights this has provided about the current political situation in this country have been illuminating.

The first incident occurred while I was walking to breakfast one Saturday morning and I encountered two men having a heated discussion over money. I only caught about 30 seconds of it as I passed them on the sidewalk, but that was enough for me to know that the two men were acquainted enough for the one to loan the other money to cover some household expenses, that the loaner was in anxious need of being repaid to cover some of his own, and that neither of them were adequately employed to cover everything. Indeed, I recognized the shirt uniform of a local grocery store on the loaner, providing me with a very realistic idea of his likely weekly income. It was clear there was no danger of things escalating to physical violence, but it was also equally clear that the attentions of these men were wholly occupied with their financial dilemmas and nothing else.

That’s when the insight struck, unbidden: the economic realities of their lives pretty much precluded either of these men from having the time or energy—the luxury—of concerning themselves with the current political situation in this country. Daily survival was consuming all their attention, and as Maslow wisely observed, until you have met basic physiological and safety needs, there are absolutely no additional inner resources for anything else. Concerns about democratic norms and Trump’s authoritarian behaviors are meaningless white noise to someone apprehensively worried (if not panicked) about food, clothing, and shelter.

Now, I had never considered the notion that civic engagement might be a luxury—a privilege—but as I recalled an incident in my own early adult life where I made a very stupid financial decision that forced me to eat nothing but cooked white rice and unseasoned lentils for a month (and I wish I was joking or exaggerating), I realized that of course such engagement is a luxury! We can talk all we want about responsible citizenship, but as an individual, I or anyone else must have the additional resources beyond survival and safety before someone can literally afford to take on that responsibility. As an affluent white male, I can express my outrage at the Trump administration all I want and as loudly as I want because my economic status more than meets my basic needs. I have the privilege of being pissed off.

But that got me to wondering how many other people in our society find themselves in the same situation as the two men I encountered, and while the answer is, frankly, a “moving target”—some surveys have the percentage of households living paycheck-to-paycheck as high as 62%, some as low as 34%—the most conservative evaluations done by Jeffrey Fuhrer of the Brookings Institute identifies 43% of American households as unable to meet the benchmark of what he calls “the cost of a basket of basic necessities.” In other words, for nearly half the families in the United States, their total monthly incomes do not cover the cost of paying for the fundamental necessities to meet Maslow’s physiological and safety needs.

Which means that a disturbingly high number of people in this country simply do not have the necessary luxury to worry about the fate of their immediate communities, let alone the fate of the nation or something as abstract as “democracy.” Add in the fact that these individuals therefore also do not have the extra “bandwidth” to be sorting the disinformation and misinformation flooding their lives, and the state-of-affairs right now in our society suddenly makes a lot more sense to me than it did a couple of weeks ago: if you are truly a “have-not,” then the only “truth” that can matter is whatever enables you to be less “not.”

Granted, that may sound awfully cynical of me. But like I said, I remember my own beans-and-rice moment, and I know for a fact that I did not spend a lot of that month worried about the Iran-Contra Affair of the Reagan presidency.

Yet, what those in the MAGA movement might be more likely to accuse me of than cynicism is elitism, and that brings me to my other experiential insight of the recent past. Again, another breakfast. Only this time, the unbidden thought came as I was reading an article about black holes. Apparently, the gravitational well of the super black holes at the center of galaxies can slingshot actual stars through space at tremendous velocities, and in fact:

S5-HVS1 was the first confirmed such hypervelocity star, and it’s moving at more than 1,700 kilometers per second. Feel free to take a moment to absorb that fact: an entire star has been ejected from a black hole at more than six million kilometers per hour [four orders of magnitude faster than the 4,200 km/hr of the fastest bullet]. The energies involved are terrifying (Plait, p. 84).

I learned further that the Large Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy orbiting our own has its own super black hole and is consequently effectively “shooting stars at us!” Granted, the asteroids in our own solar system are far more problematic (ask the dinosaurs!), but still….

I know; I digress. Back to my unbidden thought. Or perhaps I should I say thoughts, plural. First, here I sat with the time and leisure to read something interesting that had no practical value to my physiological or safety needs. Second, I also had the benefit of a level of education that enabled me not only to comprehend this article but to have the consequent and correlating cognitive capacity to parse and analyze the very threats to democracy and our social order that the Trump administration now presents. In other words, I can be outraged at Trump’s actions because I can fully understand what the consequences of them are. Again, I possess the privilege—of a different kind—to be pissed off.

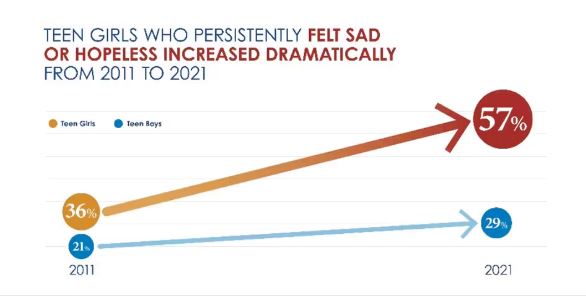

Now, education should neither be a “luxury” nor a “privilege”—especially in a democracy!—yet sadly, the historical record in this country reveals that education has seldom been an absolute right for everyone in the population. The closest we probably came was in the post-war years following WW2, with the GI bill and Brown vs. the Board of Education (along with some other curricular reforms such as “the new math”). But even those efforts often faced heavy resistance or were not equitably distributed, and by the end of the school busing conflicts of the 1970s and the rise of the Reagan era in the 1980s, an unbiased, just, and equivalent education for “all” began once more to be a “right” of only the more affluent.

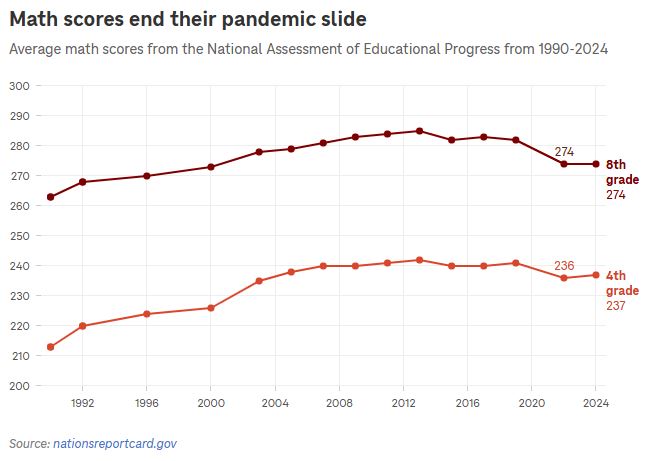

Not that there weren’t significant efforts to change this trajectory. The “No Child Left Behind” and the “Every Student Succeeds Act” were national legislative efforts to improve America’s schools—as were the creation of the Common Core set of national educational standards for literacy and numeracy. But, too often, the assessment methods of these efforts ended up being either punitive in character (with poor urban and rural school districts frequently taken over by state boards of education) or publicly unpalatable (the Common Core demonstrating how badly devolved critical thinking skills had actually become in the U.S.). Thus, by the time of the pandemic, an equitable education for all in this country had been on a steady decline for over a decade, and even where it was happening (as Mehta & Fine demonstrated), the quality was at best mediocre.

And we all know what happened next.

Which brings me back to my unbidden thoughts of these past few weeks. First, they are obviously correlated. One’s level of education and one’s economic security go hand in hand, and so it should not be surprising to find so many people in our society dispossessed of the “privilege” of civic engagement—nor the rise in authoritarianism that comes with that. Second, my newfound awareness that civic engagement is in any way or to any degree a privileged luxury that not everyone in our society has full, unfettered access to frankly horrifies me—it is not a truth I am thrilled or excited to learn. But, third, now that I am aware of my additional privilege, it is incumbent on me to employ it as best as I am able to combat the negative changes I see today in our society, and I believe where I can do that best remains for now the classroom.

Moreover, the reason why I believe that this is true is because of the life and work of fellow educator, Paulo Freire. For those not familiar with him, Freire revolutionized the teaching of reading in his native Brazil, empowering once illiterate farmers and dayworkers in his country to confront the authoritarian power structures of their day, and so successful were Freire’s efforts that he was exiled by the 1964 military junta. However, the seed he planted remained, and a little over a decade later, he returned to his native land, where his literacy efforts would one day lead to some of Brazil’s first democratically elected governments. Today, the power of that educational legacy remains, and Brazil’s democracy has recently survived (and imprisoned) its own Donald Trump. Thus, never doubt what the power of the written word and the education it provides can do.

Nor, for that matter, the power of those who can—and still do—read. I keep writing my hope for a reason.

References

Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: The Continuum Publishing Company.

Fuhrer, J. (June 20, 2024) How Many are in Need in the US? The Poverty Rate is the Tip of the Iceberg. The Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-many-are-in-need-in-the-us-the-poverty-rate-is-the-tip-of-the-iceberg/.

Mehta, J. & Fine, S. (2019) In Search of Deeper Learning: the Quest to Remake the American High School. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Plait, P. (Sept. 2025) The Black Hole Next Door. Scientific American. Pp. 83-84.

Srikant, K. (Feb. 26, 2025) Fact Check: Is there a consensus that a majority of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck? Econofact. https://econofact.org/factbrief/is-there-a-consensus-that-a-majority-of-americans-are-living-paycheck-to-paycheck.