For the light shines in the darkness,

and the darkness has not overcome it.

—John 1:5

It happened. It finally happened.

I will remember Monday April 19, 2021 for the rest of my life.

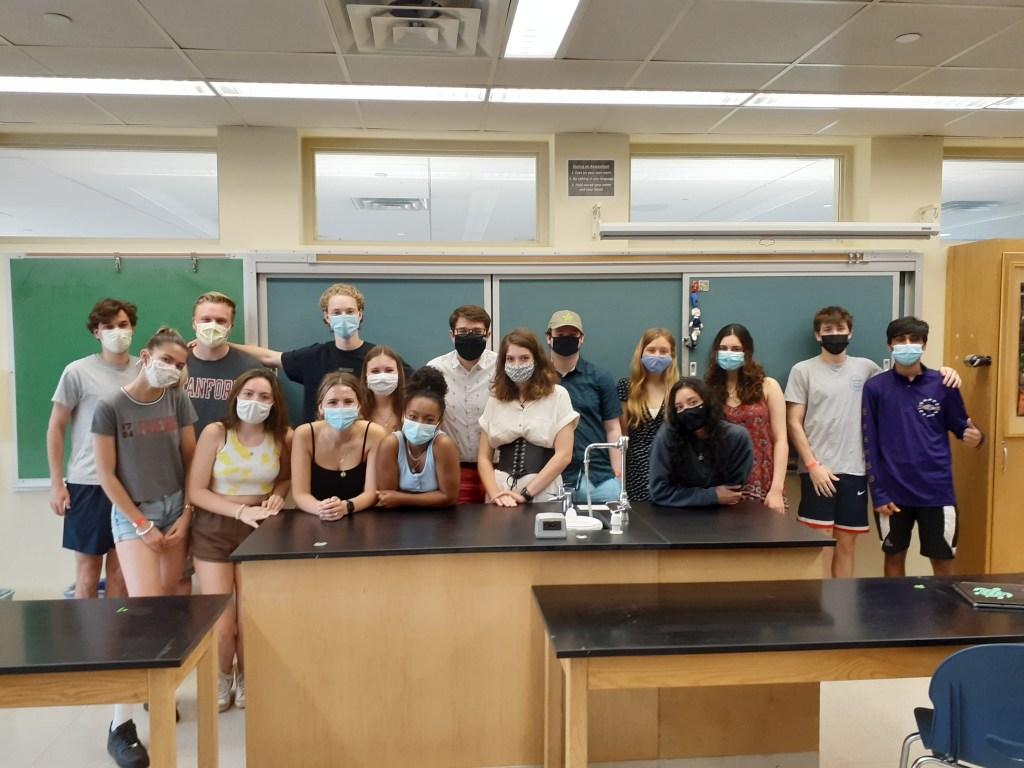

For the first time in the 227 days since the start of school (and in my case, 22 months and 18 days), I taught a class totally live. No Zoom. No virtual. Eleven bodies in the class; eleven bodies in the room.

Then it happened again, with another class. And yet again, with yet another class!

I have seldom felt more gloriously and totally alive as an educator.

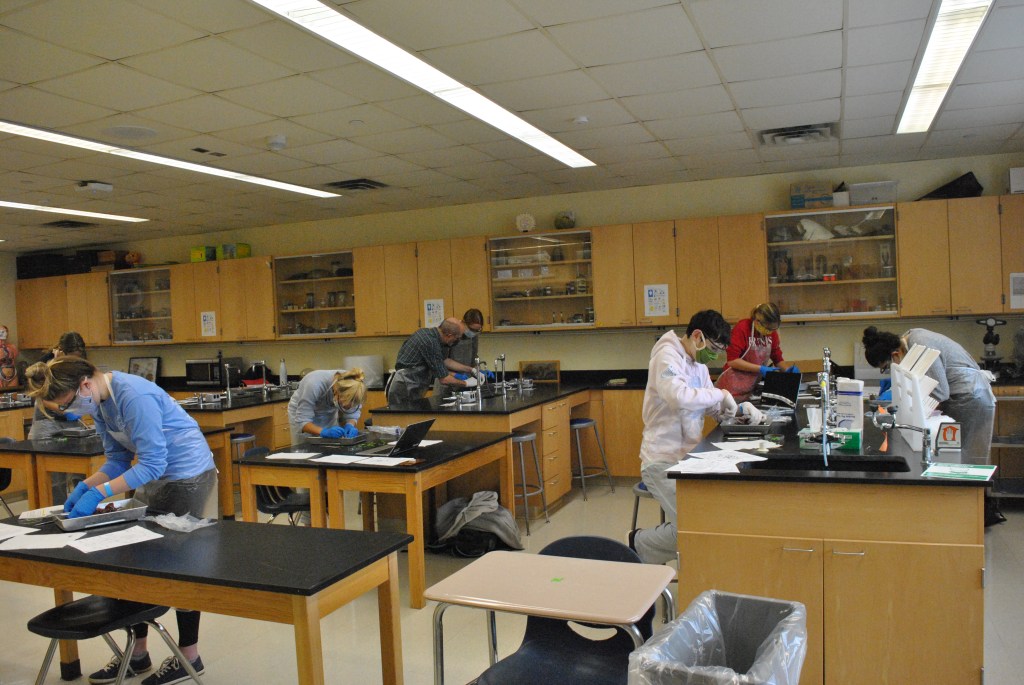

Of course, none of it lasted. I was back to virtual and zooming at least one or two students into hybrid by the very next class, and in the case of my two senior courses, it was only a week before they left for their month-long work projects. But for a total of 180 minutes the last two weeks of April, I had the chance once more to be truly authentically engaged as an educator and not have to compromise nearly everything I know about good teaching.

And that has been my greatest challenge this school year: the soul-searing compromise. Having spent the better part of a year on sabbatical reflecting, researching, and writing about the qualities of good teaching and learning, only to find myself in a situation where it is simply not possible to practice nearly any of it…the emotional cost of my necessitated and deliberate hypocrisy has been severe. It has made getting up each morning to enter the classroom taxing and wearing, and for the first time since very early in my career, when I was striving—not always successfully—to master my craft, I am eager for a school year to come to an end.

Nor am I alone in my feelings. I have already written about the hiring crisis facing education today (made only worse by the pandemic). But a year of “zoom zombies” and the exhausting concessions that hybrid teaching demands has only inflamed this crisis even further, and while my sample size is limited, I have heard quite a few colleagues declare that they simply will not return if learning is not back to in-person again this coming fall. They won’t do it to themselves; they won’t do it to the kids.

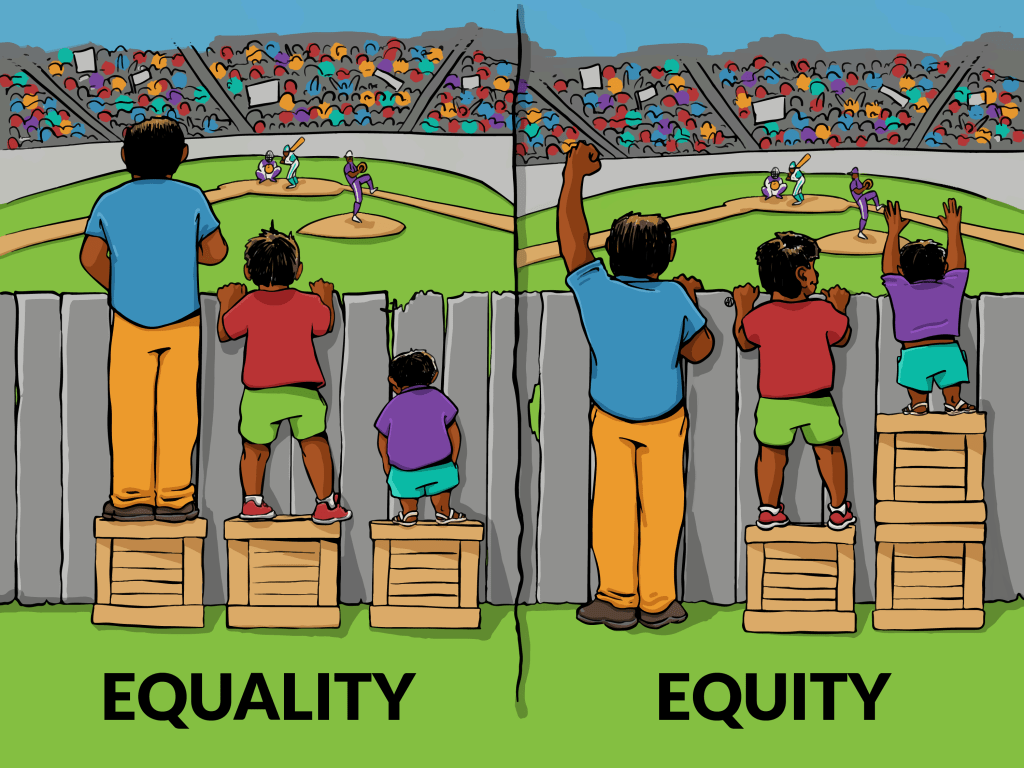

And children everywhere have paid a price. Just here in Maryland, failure rates among high school students have doubled in 11 of the 24 school districts in English and have doubled in 13 of them in math. In fact, 61% of all students throughout the state are failing at least one course, and many students who were once earning “A’s” and “B’s” are now earning “C’s” and “D’s.” Daily attendance has plummeted, with levels as low as 56% among those who were already disadvantaged even before the pandemic, and from Las Vegas, Nevada to Broward County, Florida “experts say it could take years to make up the ground that has been lost” (Bowie)—assuming it can be made up at all (see The Tally So Far).

Yet lest the doom and gloom get too dark (and my readers question my sanity, wondering how my recent joy in the classroom could cause me to appear to go there so quickly in the first place), I want to suggest that my brief return to authentic engagement with my students and my inability to be so engaged for most of this academic year is one of those both-and paradoxes that points to a larger truth that is critical not only for those of us who teach but for everyone everywhere: that life is messy. Sometimes, like now, it is messier than at others. But there is always something—some obstacle, some task, some relationship, some event, some natural law—something! that forces us to adapt to it and not the other way around. Something requiring our attention that we find inconvenient or unpleasant or undesirable and that there is nothing we can do about it except deal with it because we have no control over the reality of its presence in our lives. Life is just messy.

However, we live in a society that doesn’t like to acknowledge this fundamental truth. Nor do we like to acknowledge its corollary: that damage happens to all of us. It is simply not possible to walk this journey we call life and remain undamaged. We all bear and live with scars, and the situation with the pandemic is not going to be any different. As a natural disaster, it is going to leave damage in its wake, and some of that damage will be irreparable. Lives have been lost; lives have been upended; lives have been changed forever; and we are all going to have to live with that going forward.

But that’s the point. Seeing all my students together for the first time reminded me of all the resilience, fortitude, and perseverance it has taken them and me to make it through our educational journey this past school year. They reminded me that because life is messy and we walk through it carrying the scars from that mess with us, it is how we walk that matters. For some, the messiness and damage of life are overwhelming, and they walk defeated and despaired. For others, the messiness and damage of life are simply part of its challenge, and they walk effective and engaged. My students being completely in-person reminded me that I’m trying to be part of this latter group.

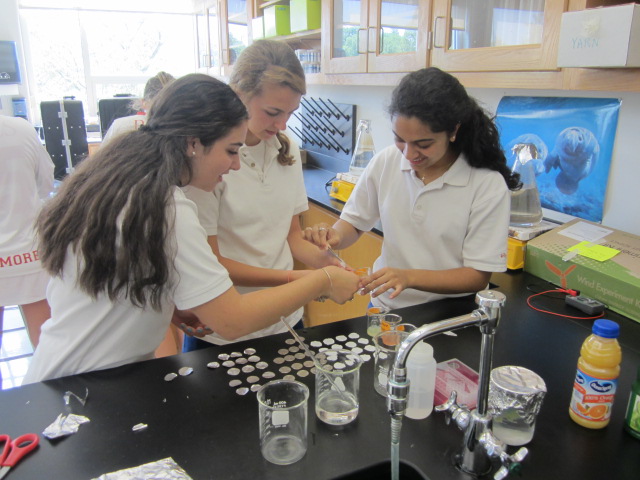

What, though, causes some individuals to walk confounded by life’s messiness and damage while others don’t? It turns out that the group I aspire to be a member of possess a set of properties that psychologists now often refer to collectively as “grit,” and what is interesting to me as an educator is that we now know that grit can be taught. Through a proper combination of deliberately induced stress (see Chapter 3) and nurtured growth-mindset (see Chapter 6), individuals can learn both to navigate and to manage the truth that life is messy and that no one lives undamaged and to do so quite effectively. Indeed, developing grit in students has been shown to help them thrive even in the face of life’s darker realities.

Of course, the challenge for schools is that this proper combination has to involve intentional moments of failure, and because we insist as a society on grading people to rank them, such failure doesn’t sit too well with the larger community—in spite of the mountains of data that show that possession of grit is the key identifier in a child for future success. In addition, as I have laid out in more detail in Parts One and Two of “The Unprepared Generation,” we have created a digital cultural in today’s world that actually undermines peoples’ capacity to learn grit. Hence, we have not exactly been doing a good job in education when it comes to grit—which together with our failure to achieve science literacy in this country probably explains a lot about how badly we have coped with the virus.

Yet, if there is possibly a positive outcome from this pandemic, it may be the fact that it has forced all of us to nurture the resilience, perseverance, forbearance, delayed-gratification, etc. that are the very heart of grit. My chance to authentically engage with students again—even for only a few hours—allowed me to see the change that tells me that they have all gotten a little “grittier” these past 14 months and that they have learned how to shine their inner light a little brighter against life’s messiness and damage. Moving forward, that can only be a good thing for everyone.

I just wish I could have been a better teacher for them along the journey.

Coda

Or maybe I was a better teacher for them than I thought. While writing this posting for this project, something utterly unexpected happened that I am still processing, and it involves my current seniors.

For one of my sections, their last class of high school on their last day of high school was with me, and as I have done now for over twenty years, I closed class by thanking them for allowing me to be their teacher (it’s an elective after all) and to share my appreciation for all the hard work they had done. I was preparing to say goodbye when the entire class abruptly sat up very straight, and one of my students who had clearly been designated the spokesperson declared “We have something for you, Mr. Brock.” She proceeded to give me card they had all signed and gave a short speech about how grateful they were to have had me as their teacher and how positive an impact I had had on all of them, and then the entire class called out in agreement.

I was dumbfounded. Still am. For those who recall my story of “The Class from Hell,” well, this has been the year from hell. And much as I did while teaching that class, I have spent the past eight months feeling utterly inadequate as an educator. It has been like revisiting those first few years of teaching where—as one fellow educator once said—“you just want to go back and apologize to all of them for the job you did.”

But those who do recall the story of “The Class from Hell” will also recall my student, John, and his evaluation letter at the end of that year in which he shared with me that I had impacted his life for the better. I remember at the time thinking that what he was writing could not possibly be true, and I have that exact same feeling again right now about the gratitude of my current students: it simply does not seem possible that my subpar performance as an educator under the conditions at school this past year could have made a difference for good in their lives.

Apparently, though, it did—at least to some degree—and that, I think, is the ultimate lesson my seniors have to teach all adults and why I share this final story: as grownups, we must never forget that we are always having an impact on the children in our lives; hence, we must always remember to strive to make it as positive a one as possible. They are paying attention, and we never know when they may be watching. So we owe them our best—even when that best may feel to us like only “good enough.”

References

Bowie, L. (April 25, 2021) The Big Cost of Learning Online: The Number of Maryland Students Who Are Failing Has Soared During the Pandemic. The Baltimore Sun. https://www.baltimoresun.com/education/bs-prem-ed-grades-failing-double-20210422-bgncuh2glna6perfw6y4ya22su-story.html.

Dweck, C. (2016) Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Ballantine Books.

Tough, P. (2012) How Children Succeed. Boston: Mariner Books.

Warner, J. (April 13, 2021) Parents, Stop Talking About the “Lost” Year. The New York Times. https://www.thetimes-tribune.com/parents-stop-talking-about-the-lost-year/article_fca787d3-42bb-5bac-b063-aad59fda5a30.html.

Whitman, G. & Kelleher, I. (2016) Neuroteach: Brain Science and the Future of Education. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.