Treat people as if they were what they ought to be

and you help them become what they are capable of being.

—Goethe

I have never been more afraid for America’s future in my life.

—Thomas Friedman

In the original TV series, Dragnet, the character Sgt. Joe Friday is alleged to have said “Just the facts, ma’am.” But like Bill Clinton’s association with “it’s the economy, stupid,” it is a total fabrication. The famed comedian, Stan Freberg, said something similar in his parody of the show, and what would now be called a meme was born, with “just the facts, ma’am” forever associated—incorrectly—with Joe Friday. However, just as the meme connected with former President Clinton served as a useful lens for an earlier essay about education in this country, “just the facts” is an ideal one with which to start this posting; so here are just a few of the most relevant ones:

- 40% of fourth graders today read below the basic level on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), meaning that they “cannot grasp the sequence of events in a story.” It is the worst performance for this grade-level in 20 years.

- 33% of eight graders today also read below the basic level on the NAEP, meaning that they “can’t grasp the main idea of an essay or identify the different sides of a debate.” It is the worst performance for this grade-level in the five decades since the inception of the exam.

- In terms of reading engagement outside of school, 34% of fourth graders now report that they read only 30 minutes or less each day, and though a mere 34% of eighth graders reported reading for fun in 1984, that number has now dropped to 14% in 2023.

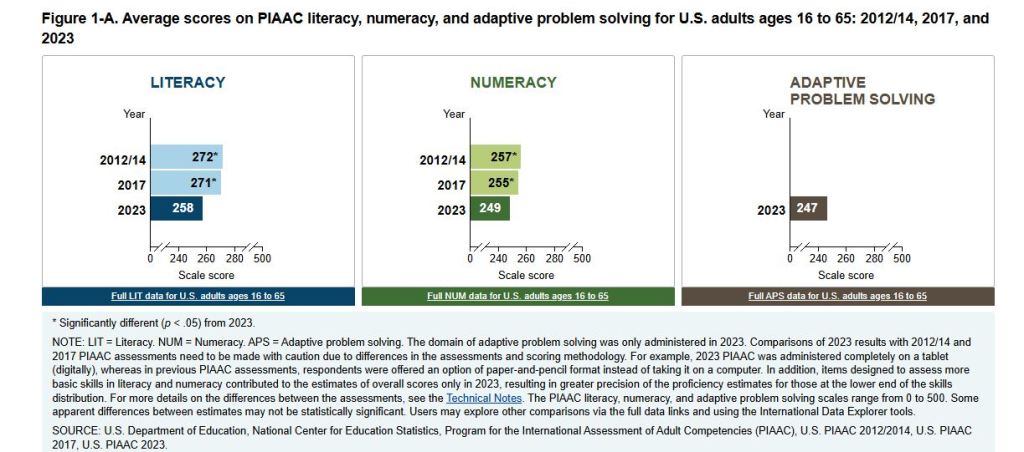

- As for the United States’ adult population, 30% of them can only read at the level of a 10-year-old, and both numeracy and literacy levels as measured by the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies have dropped consistently among those ages 16-65 (see graphic).

Now since literacy of any kind is the foundation for the ability to reason and the basis for all background knowledge needed to make good decisions in a complex world, then these facts are extremely problematic—and that is a very generous understatement. As New York Times columnist David Brooks puts it—quoting retired generals Jim Mattis and Bing West—“if you haven’t read hundreds of books, you are functionally illiterate, and you will be incompetent, because your personal experiences alone aren’t broad enough to sustain you.” Reading—and lots of it—is the keystone to our capacity for critical reasoning, and just as the absence of a keystone species in an ecosystem will lead to its collapse, the absence of reading in a country’s population is a recipe for the breakdown of our entire social order.

And before I am accused of hyperbole, I am already witnessing the potential for this breakdown in my own classes and have been now for over a decade. Like Anya Galli Robertson, who teaches sociology at the University of Dayton, I too have continued to “give similar lectures, assign the same books and give the same tests that [I] always have,” and like Professor Robertson, I too have seen firsthand how “years ago, students could handle it; now they are floundering.” Moreover, while the mental coddling I’ve written about before is definitely playing a role in this situation, the even bigger causal source for this general decline in my students’ collective IQ, CQ, and EQ is their poor reading habits. Habits due in no small degree to the amount of screen time spent on their phones.

Also (to quote Brooks again):

Not just any screen time. Actively initiating a search for information on the web may not weaken your reasoning skills. But passively scrolling TikTok or X weakens everything from your ability to process verbal information to your working memory to your ability to focus. You might as well take a sledgehammer to your skull.

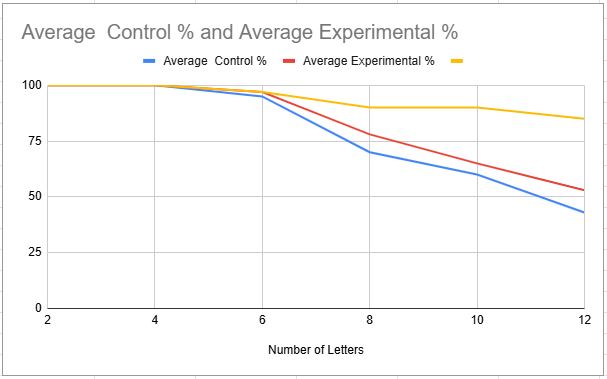

Or more accurately, a broom. To see why, a little brain science from my own classroom is in order. Each year around this time, I have my senior anatomy class perform a series of experiments. I give them a standard short-term memory (STM) test in the absence of their cellphones; we do a few other learning activities; then they take the exact same test a second time while grasping their phones in their hands after playing with their devices for two minutes. Data is scored, loaded into the spreadsheets, and then we wait until the next class where we do the exact same sequence of events with a different but equivalent STM test—only this time, no phones are present at all. Again, data is scored, and I “innocently” ask how many of them scored better the second time—to which every hand in the room rises, and I use this fact to introduce the concept of working memory.

Put simply, working memory is like a temporary storage shelf that your hippocampus uses to place items from your immediate STM that you might want to add eventually to long-term memory (LTM). It’s a parking lot for thoughts and experiences needing evaluation as to whether they are important enough to dedicate to your LTM, and it’s why you can recall what you had for dinner last night—something that is no longer in your current STM awareness—but cannot say what you had for dinner a month ago (unless you have one of those extremely rare autobiographical memories). Basically, your working memory still has last night’s dinner on its shelf waiting for processing while nearly every previous meal you’ve ever eaten has been swept from the shelf as not having enough significance for LTM (again, those special ones you do remember got the required import tag).

Having taught all this to my students, what I do next is bring up the graph below, and this is when their eyes all widen and why I do not, like David Brooks, have to say “so the main cause is probably screen time” (my emphasis). The blue line represents the impact on STM of asking it to store and recall increasingly longer sequences of random letters. It is the averaged student data from the very first STM test, and it is exactly the trend neuroscience would expect. The yellow line represents what neuroscience says should have happened after my students took the exact same test a second time that first day (and which did happen with the second STM test). The red line, though, is what happened when my students were holding their phones after playing with them while taking the exact same test a second time: the mere physical presence of the devices wiping their working memories clean. Groundhog Day for the brain, every day, 365 per year.

Anyone not unnerved at least a little by this data about our devices is probably not reading this essay in the first place, but if not convinced, then, like David Brooks:

My biggest worry is that behavioral change is leading to cultural change. As we spend time on our screens, we’re abandoning a value that used to be pretty central to our culture — the idea that you should work hard to improve your capacity for wisdom and judgment all the days of your life. That education, including lifelong out-of-school learning, is really valuable.

However, as I reminded my seniors this year, let’s be generous and assume anyone reading this essay gets that our society’s changing habits about reading and learning may be endangering our very future. Then the logical question to ask next is: how our society is handling this potential crisis? Again, “just the facts” can be useful:

- The Baltimore City Public Schools have had to close their tutoring program for reading remediation for 1,100 students because of the withdrawal of $418 million dollars in promised pandemic recovery funds (as a district, they will not be alone).

- The former CEO of World Wrestling Entertainment—the “apotheosis” of demanding intellectual engagement!—has been confirmed as the next United States Secretary of Education, with the explicit charge to dismantle and destroy the entire department (the executive order was signed a month ago).

- Harvard University has lost more than $2 billion in federal research funds for having the temerity to basically say that critical thinking matters (with additional threats to their tax-exempt status on the line).

- And, finally, as a country, we have ceded to China the global leadership in research output in the fields of chemistry, physics, and earth & environmental science (with biology and the health sciences soon to follow due to the recent defunding of the NIH and the firing of many of their scientists).

That last fact may be the most telling one, and it is why I was sorely tempted to title this essay “The Stupidifying of America.” Our collective education system in this country no longer produces enough “home grown” PhD scientists and engineers, as well as other levels of expertise, to meet our most basic economic needs, and the “cruel farce” that is the Trump administration is simply going to make things worse. As Thomas Friedman points out:

Do you know what our democratic allies do with rogue states? Let’s connect some dots. First, they don’t buy Treasury bills as much as they used to. So America has to offer them higher rates of interest to do so — which will ripple through our entire economy, from car payments to home mortgages to the cost of servicing our national debt at the expense of everything else…[Thus] bond yields keep spiking and the dollar keeps weakening — classic signs of a loss of confidence that does not have to be large to have a large impact on our whole economy…[Furthermore,] you shrink all those things — our ability to attract the world’s most energetic and entrepreneurial immigrants, which allowed us to be the world’s center for innovation; our power to draw in a disproportionate share of the world’s savings, which allowed us to live beyond our means for decades; and our reputation for upholding the rule of law — and over time you end up with an America that will be less prosperous, less respected and increasingly isolated.

Like Friedman, I am truly frightened for our country, but like Goethe, I know what I need to do in my small corner of influence to combat the rising tide of ignorance, anti-intellectualism, and antipathy. As the sign at one of the Hands Off protests suggests, I’ll keep teaching critical thinking to my students—in the hope that future elections might turn out for the better.

References

Bowie, L. (April 4, 2025) Baltimore Schools to Cut Tutoring and More After Trump Administration Backtracks on Funds. The Baltimore Banner. https://www.thebaltimorebanner.com/education/k-12-schools/baltimore-city-schools-federal-funding-AM5PH4I6G5B3PCG66S6RC3IKDE/.

Brooks, D. (April 10, 2025) Producing Something This Stupid is the Achievement of a Lifetime. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/10/opinion/education-smart-thinking-reading-tariffs.html.

Friedman, T. (April 15, 2025) I Have Never Been More Afraid for My Country’s Future. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/15/opinion/trump-administration-china.html.

Lukianoff, G. & Haidt, J. (2018) The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. New York: Penguin Books.

Nation’s Report Card (2025) National Assessment of Educational Progress. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/.

NCES (2023) Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/piaac/2023/national_results.asp.